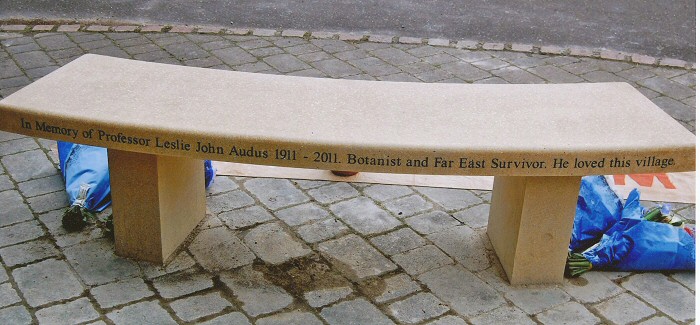

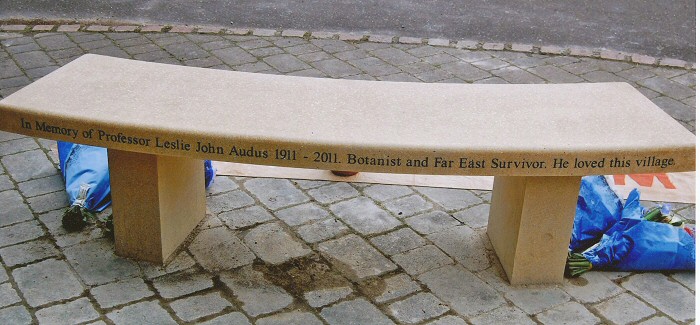

Seat

dedication in Leslie's boyhood village, Isleham, Cambridgeshire, 9

June 2012

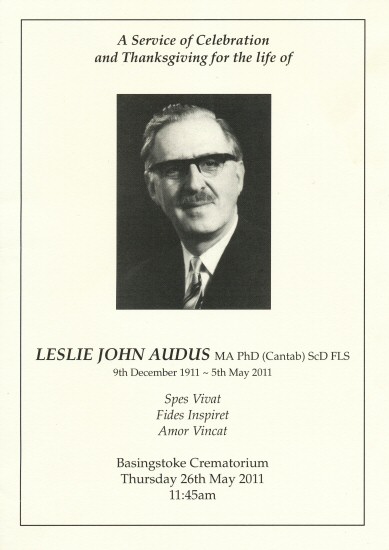

Service of Celebration, 26 May 2011

Obituary

in the Daily Telegraph, Friday 13th May 2011

Leslie Audus the scientist

Fiona Pushman, Leslie's daughter, writes: 'Isleham was not

only where Leslie was born and raised, but it remained a place that

mattered to him throughout his long life. So the family wanted to have

something permanent to commemorate this lasting link.

On one visit when Leslie walked around the village with

Chris and me, we rested for a while on a memorial bench. This seemed so

suitable, in keeping with the village and we were pleased that the

Parish Council have approved our request for a similar bench in his

memory.

Therefore, on 9 June 2012, Leslie’s ashes will return to Isleham. At

11:15 am a bench will be dedicated to his memory at the top of Pound

Lane (opposite The Griffin) and at 11:45 his ashes will be

interred in the Isleham Cemetery .

There is also an area (just under an acre) of Priory Wood

at Burwell dedicated to his memory, but the Woodland Trust site does not

allow for any actual dedication plaque so is only known to those who

know!'

We are grateful to Fred Eden, a wartime schoolboy at Soham

Grammar School, for attending on behalf of the Soham Grammarians and for

these photos of the occasion.

The seat is inscribed

In Memory of Professor Leslie John Audus 1911-2011. Botanist and Far

East Survivor. He loved this village.

Leslie's daughter Fiona (4th on left) and members of Leslie's family at

the seat.

The Welcome Home banner was put up by Leslie's mother for the day he

returned from captivity in the Far East.

Fred Eden SG44 is the one wearing the Soham Grammarians tie.

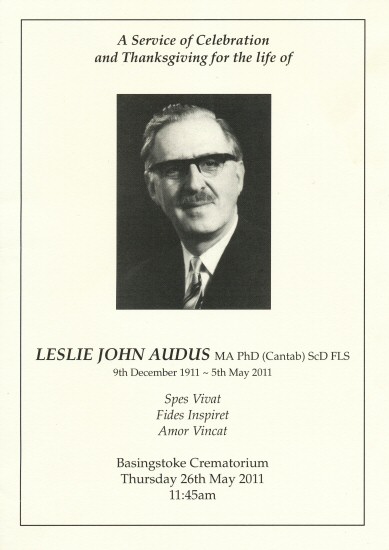

Leslie Audus died aged 99 on 5th May

2011 and was cremated on Thursday 26th May 2011. The service of

thanksgiving to celebrate his life was held at Basingstoke

Crematorium, followed by a buffet lunch at Bolton Arms Old Basing.

A Service of

Celebration

and Thanksgiving for the life of

LESLIE JOHN AUDUS

MA PhD (Cantab) ScD FLS

9th December 1911 - 5th May 2011

Spes Vivat

Fides Inspiret

Amor Vincat

Basingstoke Crematorium

Thursday 26th May 2011

11:45am

|

|

Order of Service

Entry Music

Mahler - 5th Symphony - Adagietto

Welcome

Jeremy Caddy - Funeral Celebrant

Introduction

Hymn

Abide with me; fast falls the eventide

Tribute

Early Life [to be added]

Music

Linden Lea

Soloist Joan Warren with Harp accompanist Judith Philip

Tribute

POW Years (1942 - 1945)

Followed by music

Brahms Piano Concerto B flat Major - 4th Movement

Tribute

FEPOW by Meg Parkes

Followed by FEPOW Prayer

The following tribute, written by RAF Medical Officer

Richard Philps at the start of his memoir, Prisoner Doctor

was published in 1996:

“The men who survived Haruku and subsequent camps have

reason to be extremely grateful to Leslie J Audus, Professor Emeritus

of Botany at London University. Professor Audus was with us as a

prisoner, having joined the Royal Air Force as a scientist and become

a Radar (then called Radiolocation) Officer.

During our first critical time at Haruku, with deaths

from beriberi mounting and blindness from Vitamin B deficiency on the

increase, he, at first single-handedly, and later with a Dutch

botanist, Dr (now Professor) JG ten Houten, devised a method of

producing yeast, an abundant source of Vitamin B.

This was against almost impossible odds and with the

most primitive equipment, but it was so successful that the onset of

blindness was halted in those already affected, no new cases occurred,

and other changes due to Vitamin B deficiency began to improve – a

remarkable feat of biological manipulation.”

I would add to Dr Philps’ words that those of us with an

interest in FEPOW, that is Far East Prisoner Of War, history, be it

academic or family-inspired, also owe Leslie John Audus a huge debt of

gratitude.

Not only did his expertise and practical ability save

countless lives between 1942 and 1945, but by committing his

experiences to print as he later did, he ensured that future

generations would also gain a better understanding of the

circumstances of their survival.

After their liberation and repatriation during the

autumn of 1945, most FEPOW found it very difficult to share their

experiences with others. They were not encouraged to do so; some men

never did. As a consequence, even today their part in World War Two

history is still relatively little known.

The public perception of Far East captivity is generally

centred around the building of the railway through the jungles of

Thailand and Burma. But thanks to Leslie’s decision to publish a paper

in 1946 entitled, Biology Behind Barbed Wire, in the

scientific journal Discovery, the facts were set out while

they were still clear in his mind.

This article became the basis for a book about Far East

captivity in the Moluccas (commonly known as the Spice Islands),

published initially by Dutch prisoners of war. Years later this book

was translated into English by Leslie and became Spice Islands

Slaves. Now we could learn about the equally appalling

circumstances endured by over 2,000 British FEPOW who were shipped

from Java to build airfields on the Spice Islands in April 1943 –

truly a voyage into Hades.

I first met Leslie in 2003 when I bought his book

through the Java FEPOW 1942 Club. He was a

long-standing and valued member of the Club (and also the London

FEPOW Club). Indeed, some of the other Java Club FEPOWs had

directly benefitted from his ingenuity and skill. I had just recently

joined the Java Club and was attending the annual meeting in

Stratford-upon-Avon. My interest in this history stemmed from my

father’s FEPOW captivity in both Java and Japan (though to my

knowledge, the two never met).

I subsequently had the great good fortune to visit

Leslie on two separate occasions at home in his Earl’s Court flat,

where I listened to his vivid recollections of those days. He showed

me some of his vast collection of drawings and memorabilia, recorded,

hidden and eventually brought home.

What a treasure trove!

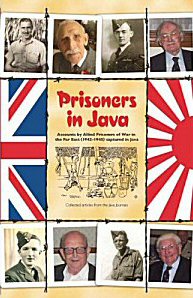

In 2006, Leslie wrote a Foreword for the Java FEPOW

Club’s book, Prisoner in Java, a compilation of articles

extracted from twenty-two years of the Club’s quarterly newsletter, The

Java Journals. The Club not only looks after the few remaining

FEPOW veterans, but also their widows. Both the book, and the ongoing

work of the Club, honour all these courageous men and women.

My own interest has grown into academic study and I am

based at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. During the

research for my dissertation, I came across an interview that Leslie

gave, in August 1986, aged 75, to Dr Charles Roland from McMaster

University in Ontario. I quote:

“… mental attitude played such a vital part in

survival. This is why I think

I’m so lucky in that I had something to interest me. I had this

yeast-stuff to make…”

Something of an understatement, I would say.

In January 2009, Leslie agreed to give me an interview

about his long-term perspective of those years in captivity, as part

of the Liverpool Tropical School’s FEPOW oral history study. It was

such a privilege to listen to and record his recollections.

On behalf of all the members of the Java FEPOW 1942 Club

- FEPOW history researchers everywhere - and from me: Thank You,

Leslie.

THE FEPOW PRAYER

by

FEPOWs Cpl Arthur E Ogden and Victor Merrett

And we that are left grow old with the years

Remembering the heartache, the pain and the tears,

Hoping and praying that never again

Man will sink to such sorrow and shame.

The price that was paid we will always remember

Every day, every month, not just in November,

We Shall Remember Them.

Tribute

Academic Years (1948 - 1979) by Professor WG Chaloner

[items in italics were in Prof Chaloner's draft

but omitted on the day as they overlapped with what Leslie's daughter

Fiona covered]

Poem

'All is Well' by Canon Henry Scott Holland

Read by Ian Philip

Family Memories

Grandsons [to be added]

Quiet and Reflective time

The Ash Grove - Harpist Judith Philip

The Lords Prayer

Our Father, who art in Heaven,

Hallowed be Thy name;

Thy kingdom come;

Thy will be done;

on earth, as it is in Heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation;

But deliver us from evil.

For Thine is the Kingdom,

The Power, and the Glory,

For ever and ever Amen.

The Committal

Final Words

Music

Lark Ascending by Vaughan Williams

Played by Nicola Benedetti

The family would like to invite everybody

to join them after the service at

The Bolton Arms, Old Basing, RG24 7DA

for a Carvery Lunch.

Donations in memory of Leslie

if desired in aid of

'The Woodland Trust' or 'The Java FEPOW Club'

may be left as you leave the chapel or sent c/o

Co-operative Funeralcare

1 Buckland Avenue

Basingstoke

Hampshire

RG22 6JW

The family are grateful for all the comfort and support

that friends have given to Leslie over the years.

Leslie John Audus, an only child, was born on December 9 1911 at

Isleham in the fens of Cambridgeshire, a part of the country for which

he retained a deep affection for the rest of his life. Educated at Soham

Grammar School, in 1929 he won a scholarship to Downing College,

Cambridge. After completing his degree he carried out postgraduate work

until 1935.

From Cambridge he progressed to University College, Cardiff, where he

combined further research in plant physiology with teaching across a

broad spectrum of plant science. Having joined the RAFVR in 1940, he

trained in radar and in 1941 was posted to Malaya as a flight

lieutenant.

In the brief interlude before fighting hit Malaya later that year,

Audus used his free time to explore the rainforest in Johore with John

Corner (later a renowned Cambridge botanist), who was then assistant

director of the botanical gardens there.

Audus made himself popular by bringing with him a turntable,

loudspeakers and a collection of records. On the fall of Singapore, the

discs accompanied him as he escaped with his unit by ship to Jakarta. He

even managed to hang on to them after being captured there by the

Japanese, leaving them behind (with his initials scratched into the

centre of each record) only after being sent to a camp on Haruku island.

Audus’s book Spice Island Slaves (1996) records the horrors

of this time. Prisoners were forced to work in blinding sunlight to

build an airstrip from coral. As well as suffering regular beatings,

they were badly afflicted by beriberi and malnutrition-induced

conditions which affected their eyesight. Knowing of Audus’s expertise,

senior captive officers asked him to produce yeast to supply vitamins

that were missing from the men’s wretched diet.

Under conditions of extraordinary hardship, and with makeshift

equipment, Audus had first produced yeast – with the help of Dutch

fellow prisoners – at Jaarmarkt camp at Surabaya on Java. But when

transferred to Haruku he faced a problem: maize grain, which had

previously been used as a raw ingredient in the process, was not

available.

Instead he isolated a mould fungus that, in addition to producing the

needed vitamins, allowed him to manufacture an easily digestible protein

by fermenting soya beans. These supplements, together with the building

of a sea latrine that halted an outbreak of dysentery, helped reduce

prisoner deaths from 334 in five months to just 52 in the last nine

months before liberation.

On August 1 1945 Audus commanded the last party of six men out of the

camp. Ironically, however, when he was taken to hospital it was

discovered that he himself had already suffered irreversible retinal

damage. Remarkably, he overcame this disability in his subsequent

distinguished botanical career.

After the war he returned to plant physiology as a scientific officer

with the Agricultural Research Council unit of soil metabolism at

University College, Cardiff, focusing particularly on the action of

phenoxyacetic acid herbicide. From there he moved to the Hildred Carlile

Chair of Botany at Bedford College, University of London, which he held

until retiring in 1979.

There were initial difficulties: the Botany department was in cramped,

temporary accommodation with little equipment. But in 1952 it moved into

the new Darwin Building, and Audus embarked on an investigation into the

nature and mechanism of plant “hormones” (or “growth regulators”, as

they are now generally known) in roots, so resurrecting an interest in

plant responses to gravity, a research theme which had been largely

neglected for some 30 years.

The following year he published Plant Growth Substances,

which went through two more expanded editions (1959 and 1972) and became

the standard text on the subject for many years.

In 1964 he edited The Biochemistry and Physiology of Herbicides,

which was still the main reference book on that subject when he retired.

From 1965 to 1974 he edited the Journal of Experimental Botany.

Audus’s research on plant growth regulators had an impact in the

applied aspects of plant physiology, particularly in forestry,

agriculture and horticulture. This led to numerous scientific visits

overseas, and he gave advanced courses in some 15 major universities in

the United States.

He was appointed visiting Professor of Botany at the University of

California, Berkeley, in 1958; at the University of Minnesota,

Minneapolis, in 1965; and was created a life member of the New York

Academy of Sciences in 1953. Unusually for that time, he lectured

extensively in the USSR and in Poland.

For all this, Audus never neglected his departmental or collegiate

commitments. He was a fine teacher, and active in student affairs, both

social and scientific. As head of department he was approachable and

kindly. But the strength of character and tenacity that had brought him

through the horrors of war meant that he did not flinch from expressing

his views forcefully against injustice or political expediency.

His own considerable technical skill as an experimentalist also

extended to his extramural interests. He enjoyed the construction and

restoration of furniture, and built his own short-wave radio equipment

at a time when it was the only medium that enabled him to maintain

contact with former wartime comrades and fellow scientists in remote

parts of the world.

It was one such fellow prisoner who, during Audus’s time in captivity,

had managed to preserve 36 of the records he had taken out to Malaya.

Audus heard the strains of Brahms’s Piano Concerto in B Flat Major

in Jakarta after being liberated and, pointing to his scratched

signature, declared that this record and the others were his own. He

kept them for the rest of his life.

Leslie Audus married, in 1938, Rowena Mabel Ferguson. She died in 1987,

and he is survived by two daughters.

[to be added from Leslie's unpublished biography]

Leslie John Audus was born on December 11th 1911 and was educated at

Soham Grammar School, leaving, it is thought, in 1929. He went up to

Downing College Cambridge where he was Exhibitioner, 1929–31. SGS

records show he gained a Part I, Class 1, in the Natural Sciences Tripos

and that he was appointed Frank Smart University Student in Botany, at

Cambridge, 1934–35. In Summer 1937 it was reported that he was a

lecturer at Cardiff University, and had proceeded MA (Cantab) and had

obtained his PhD. Dr Leslie J Audus and Dr Rowena M Ferguson married at

Sheffield in 1938, she died in 1987. They had two daughters.

| He was Lecturer in Botany,

University Coll., Cardiff, 1935–40. During WW2 he was a Flight

Lieutenant RAFVR, serving in the Technical Branch as a Radar

Officer, 1940–46. He was PoW of the Japanese 1942-45. SG

Spring 1943: Prisoner of War: F Bye (Egypt), LJ

Audus (Java). SG Autumn 1945: Following

POWs back in England: CF Tabeart (Singapore), LJ

Audus (Java), JR Cogbill (Hong Kong)

His skills as a botanist enabled him to "save lives and the

eyesight of many men" - see

below

|

|

He was Scientific Officer at the Agricultural Research Council's Unit

of Soil Metabolism, Cardiff, 1946–47 and Monsanto Lecturer in Plant

Physiology, University College, Cardiff, 1948.

In the same year he was appointed Professor at Bedford College, London

University. The Botany Department at Bedford College had been destroyed

during the bombing of London, and the Departments of Botany and Zoology

were housed in the former mansion of a member of the gentry on the edge

of Regents Park. Professor Nielson-Jones retired and Professor

Leslie Audus was appointed in his place, and he started up

his well-known researches on the hormonal control of root growth,

geotropism, and other topics. He was Hildred Carlile Professor of

Botany, Bedford College, University of London, 1948–79.

He was Recorder, 1961–65, and President 1967–68, of Section K of the

British Association for the Advancement of Science: Visiting Professor

of Botany, University of California, Berkeley, 1958 and University of

Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1965.

He was Vice-President of the Linnean Society of London, 1959–60 and

made Honorary Fellow in 1995: Life Member of the New York Academy of

Sciences, 1961; Editor of the Journal of Experimental Botany,

1965–74.

Lesley Audus died on 5 May 2011.

Papers

by LJ Audus

from Death in the Spice Islands,

compiled by Amanda Johnston

http://www.cofepow.org.uk/pages/asia_haruku1.html

Heroes of Haruku There were many heroes in the Pelauw

camp in Haruku whose day-to-day acts of brotherhood and compassion

surely alleviated the suffering of their friends under these diabolical

circumstances. The doctors, amongst them Dr. Buning, Dr. Springer, Dr.

Philps and Dr. Bryan, saved many lives using the crudest of contrived

instruments and effecting what cures they could in the absence of

medicines or even vegetation to concoct alternative means of healing.

One of these heroes was not a doctor, but a botanist by training who

went on to become a Professor of Botany at London University some years

after the War (now an Emeritus Professor), and who was serving as a

radio officer in the RAF when taken prisoner: Leslie Audus

used his skills to manufacture yeast from 'next to nothing', providing

the very sick, and eventually all the men, with a source of vitamin B,

the absence of which in their scant diet was worsening their state of

malnutrition and causing beriberi and pellagra as well as optic

neurosis, the result of which could be irreversible blindness.

A good summary of his cultivation methods can be found in Dr. Richard

Philps' book, Prisoner Doctor as well as in his own definitive

work on the Moluccas drafts - Spice Island Slaves. Without a

doubt he saved many lives and the eyesight of many of the men by

developing his cultures, and they were most fortunate indeed that he was

in the Haruku draft where conditions were so appalling. He was only

permitted to continue with his yeast-making activities because one of

the by-products was alcohol, which was then commandeered by the Japanese

guards.

| Spice Island Slaves

by Leslie J Audus The little-publicised story of

Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in the Moluccan Archipelago

(The Spice Islands) In Eastern Indonesia from May 1943 onwards

is comprehensively recorded in this book. This chronological

history has been compiled from contemporary diaries and

records from a large number of British and Dutch sources,

including those of the author.

It is illustrated by 25 drawings of camp scenes and

personalities, maps, camp lay-outs and graphs. In those

slave-labour camps on the islands of HARUKU, AMBON (at

Liang) and CERAM (at Amahai) and during the final disastrous

attempts to return them to Java, half of the 4,110

servicemen (2,827 British and 1,283 Dutch) were to die from

starvation, disease, brutal thrashings, execution and

drownings.

The multiplicity of the sources ensure that there are no

significant gaps the story traced from from the initial

assembly of the drafts in Java to the final piecemeal return

of the living skeletons of survivors during the last year of

the war. The tragic transit camp on the island of MUNA at

the south-east corner of Sulawesi is fully covered.

|

|

ORDER FORM/CONTACT: Leslie J. Audus, c/o Lesley J. Clark, 5 Barrons

Close, Ongar, Essex, CM5 9BJ

E-mail address: Lesley Clark - lesleyclarkuk@yahoo.co.uk

PRICE: £10.25 per copy, plus UK postage & packing of £1.70 per book

(for overseas postage & packing, please add £ 4.55 for Air Mail or £

2.15 for Surface Mail)

Audus, Leslie J, Spice Island Slaves,

UK repr. 1998: Essential reading for Haruku Island, Liang, Ambon, etc.

Interesting account of synthesising vital B vitamins from rice. Good

maps and illustrations. Straightforward writing for general reader.

From RAF boy apprentice to prisoner of the Japanese, by Amanda

Johnston (WW2 People's War, BBC)

"Later, in April 1943, large numbers of men were marshalled at Jaarmarkt

Camp in Sourabaya, Java. Eric was one of 2,070 sent on a draft to the

Moluccan or ‘Spice’ Island of Haruku. Docking at Ambon in early May

1943, just before his 23rd birthday, they arrived on the muddy shores in

the monsoon season to find that they were to build their huts from

bamboo and set up what meagre facilities they could. A full account of

this and the other Moluccan drafts is given in accurate and stark detail

in the excellent book, Spice Island Slaves by Prof.

Leslie Audus, but I will continue with the bare details here.

The British commanding officer requested permission from the Japanese

to build a latrine over the sea to avoid the spread of disease. The

refusal of this request meant that the overflowing latrines and the

generally cramped and foul conditions of the makeshift camp led to a

general outbreak of dysentery, which along with the other diseases from

which the men were suffering — malaria, beri beri and diphtheria to name

a few — along with the general state of malnutrition, saw to it that of

the 2,070 men who arrived on this draft, around one fifth died within

the first few months. On top of all this, we have yet to mention their

reason for being there. They were forced by the Japanese to hack an

airstrip out of the coral of the island in order to build an airstrip

(allegedly within range of Australia). The weakened state of the men

meant that, six months into the draft, there were only around 300 to 400

anywhere near “fit” enough to go on the working parties to the airstrip.

When they were eventually allowed to build the sea latrine some months

later, the dysentery epidemic was brought under greater control and the

death rate slowed down. The Japanese sergeant responsible for this

atrocity, Gunso Mori, was later held accountable for this and other war

crimes at the post-war Far East War Crimes Tribunal and was hanged in

Singapore in 1946, along with the camp commander, Lt. Col. Anami. It has

been estimated by Prof. Audus that sadly only 40% of

those sent to toil as slaves on Haruku would have returned to the shores

of England in 1945, and Eric was fortunate enough to be one of them."

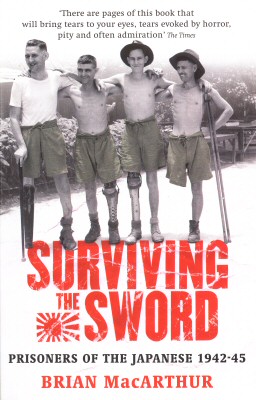

| Leslie Audus is

also referred to several times in Brian MacArthur's book - in

this link the author talks briefly about it Surviving

the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese 1942-45

.

The following extracts are reproduced by kind permission of

the author:

The book is available in the UK - Amazon.

p266 - Entertainment

The prisoners' affection for their records was shown by the

example of Flt. Lt. Leslie Audus. When he

moved to his radar station on the Malayan mainland in 1941

he took with him an amplifier, turntable, a pick-up and

loudspeakers, as well as a collection of records. After

being captured in Java, the collection was driven into

captivity, but the Dutch provided a gramophone and recitals

were given for hundreds of prisoners. When Audus was sent to

Haruku the records were left behind, but he had scratched

his name with a sharp nail on the smooth surface between the

label and grooves on every one.

When he returned to Batavia in July 1945, he heard a

familiar sound - the scratchy strains of the Brahms Piano

Concerto in B Flat Major - and was able to claim the

record as his. Thirty-six records had survived in total, and

Audus still had them in 2004 in their original paper sleeves

- a tribute, as he says, to the loving care with which they

had been preserved by an emaciated young radar officer.

|

|

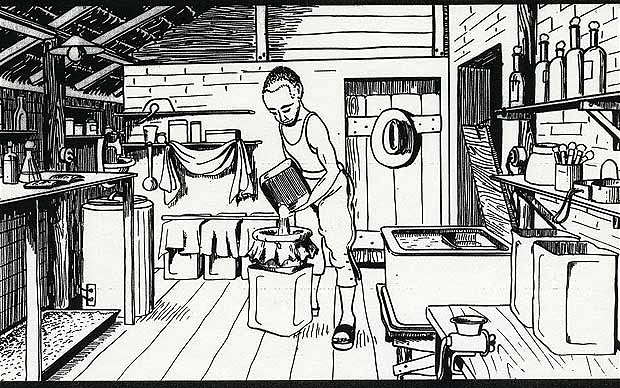

p283-286 - Ingenuity

One of the most remarkable examples of ingenuity occurred in

1944 on the Spice Island of Haruku. The men were working in blinding

sunlight to build an airfield from coral, and optical neuritis was

causing partial and even complete blindness. (See Chapter 23 for a full

account of the horrors of Haruku.) Flt. Lt. Leslie Audus,

who had just emerged from hospital partially blind himself, was urged by

Flt. Lt. Dick Philps, one of the medical officers, to start producing

yeast to provide the vitamins that were missing from the men's diet.

Audus had performed the same function earlier in Jaarmarkt camp at

Surabaya on Java.

Two Dutch prisoners, Dr van Papenrecht (who had helped Audus in

Jaarmarkt, supplying him with raw materials) and Dr ten Houten (who had

used Audus's methods on Ceram), were asked to join him. Van Papenrecht

provided his microscope, haemocytometer and a supply of reagents for

testing for sugar, and allowed Audus and ten Houten to use his

`dispensary' for experimenting.

But there was a major problem to be solved. Maize grain had previously

been the raw material in the process. But on Haruku no maize was

available. Audus's thoughts turned to his preliminary experiments in

Surabaya on the use of mould enzymes to produce a nutrient medium from

steamed rice. Picking up where he had left off in Java, he soon isolated

a mould fungus that was extremely efficient in converting starch into

sugar. This mould turned out to be Rhizopus oryzae, the

species used in the production of tempeh kedelai.

Audus described how he finally succeeded:

Kedelai is the soya bean which we were sometimes given to eat

but long boiling did nothing to make it digestible in the stomach. Dr

Pieters, an Indonesian prisoner arriving with the Amahaiers [Dutch

prisoners who had been previously been held at Amahai on Ceram],

instructed me in the method the natives use to make it digestible by

growing a fungus on it producing tempeh kedelai, a cheese-like material

which was then fried in oil. It is an acquired taste but very

nutritious. After we had acquired the technique we regularly made the

product whenever the beans were provided. The prisoners undoubtedly

profited from this protein-rich product.

Then followed weeks of crude but intensive tests to determine the

growth conditions for the mould on steamed rice and the optimum

temperature for the subsequent killing of the mould with release of the

effective enzymes. In this, fate and my dormant optimism had played a

crucial part since I still had the thermometer I had made in the

Jaarmarkt. The optimum temperature for sugar production determined

thereby turned out to be 55 degrees C. Thus encouraged we turned our

attention to finding the source of the yeast and following that deciding

the final method of bulk production and the assembling and construction

of equipment for it.

Yeast was easily isolated from the surface skin of a ripe banana by

putting a small piece in some rice digest fortified with cane sugar. The

fermentation which followed yielded a healthy suspension of yeast cells.

Bulk production started about Christmastime. For the mass production of

the essential rice/fungus mixture we simply `stole' the tempeh

kedelai technique. Wooden trays, with sacking bottoms, were

filled with inch-thick layers of steamed rice inoculated with the tempeh

kedelai fungal spores and sandwiched between layers of large

leaves to keep them moist. The fungus was left to grow for 38 to 40

hours, when it had turned the rice layer into a grey, spore-covered

'blanket' which could be lifted entire from a tray. A small portion with

its spore content was retained, dried and powdered to provide inoculum

for subsequent trays.

'Blankets' were mashed up with a small quantity of water in a large

wooden tub and the resultant `porridge' put in 25-litre earthenware

carboys originally containing soya sauce for the guards. To this

porridge was added boiling rice-washings to dilute it and bring the

temperature up to 60 degrees C. The carboys, closed with sterilised

wooden bungs, were incubated for 22 hours in 'hot-boxes', old tea chests

lined with layers of empty rice sacks, after which up to 80% of the

starch had been turned into sugar by the fungal enzymes. The digest,

strained through mosquito netting to remove fungal threads and rice cell

debris, was diluted with three times its volume of water and sterilised

by boiling. After cooling for 22 hours in large steel drums covered with

sterile sacks it was inoculated with the yeast culture. The supply of

that inoculum had been the province of Dr ten Houten who had maintained

it on a concentrated rice digest fortified with cane sugar.

The final drum fermentation lasted 48 hours and was virtually complete

by then, thanks to a massive inoculum. That milky suspension of yeast

cells was sterilized by heating to 70 degrees C for about 15 minutes in

a wajang [large iron wok], cooled and issued in 100 ml doses

to the hospital patients and, ultimately, to the whole camp. At that

time my central retinal scotomata [blind spots] had become so extensive

that all microscopic observations and cell counts had to be done by ten

Houten ... The final yield for the bulk production was 50 to 75 million

yeast cells per millilitre. That `medicine' was received with varying

degrees of enthusiasm by the prisoners since it was not particularly

palatable but, as far as I know, no one rejected it.

When the Japanese discovered his secret activity, Audus was hauled up

before Lt. Kurashima, the camp commandant, to explain why rice was being

wasted to make alcohol. When Audus explained, tongue in cheek, that

sterilisation by boiling removed all the alcohol and that the sole aim

was to combat avitaminosis, he was excused, on condition that six

bottles of the yeast suspension were provided every day for the guards.

'This we did for some days until no empty bottles were forthcoming and

the Nips had either forgotten their proviso or lost faith in the

efficacy of our product,' said Audus.

According to Dick Philps, Audus achieved a triumph against seemingly

insuperable odds. Almost single-handedly, he saved the eyesight of

hundreds of men. No cases of optic neuritis occurred after the men went

on the yeast ration. The remarkable story of how Audus, ten Houten and

van Papenrecht created yeast is an inspiring example of how prisoners in

Japanese prison camps used their scientific knowledge and ingenuity to

triumph over the most squalid and primitive conditions. Audus went on to

become a professor of botany at London University after the war.

p358 Haruku

Flt. Lt. Leslie Audus described how Mori used a cudgel of

split bamboo to beat his victims unmercifully. Kasiyama used a

doubled-up length of rope for the same purposes, 'like a crazy man'. At

the first tenko after Mori was told that his quota of prisoners could

not be met because so many men were ill, the officers were lined up

alongside the men and slapped about the head. James Home explained

precisely what this entailed: Being slapped by the Japs should not be

confused with the playful slaps that may be exchanged by Westerners ...

p360 - Haruku

Work on the airfield was hard, especially for men who weren't

used to manual labour, said Leslie Audus. The

shadowless, shimmering surface of the projected airfield was baking hot

when scorched by the tropical sun but unpleasantly bleak when it rained.

p365-372 Haruku

The number of fatalities continued to mount. By the beginning of July

200 had died. When Mori was feeling generous, he would allow purchases

for the hospital. But when one doctor got some eggs, Mori distributed

one egg to ten patients. Dr Shimada told the medical officers that if

they had no medicines, they must treat the sick with `spirit'. In Japan

nobody died of dysentery, he said. So the misery - 'filth, disease,

emaciation and death', as Audus put it - continued. By

the end of July 243 men were dead.

When Mori had sent all the men who transported food and water to the

hospital to work on the airfield in August, one doctor wrote eloquently

in his diary:

Now even more difficulties have been placed in our way, notwithstanding

the fact that the state of the sick is becoming simply frightful.

Extreme emaciation down to skin and bone, numerous infected wounds, skin

parasites; pellagra, mental disturbances, gross filthiness, chronic

diarrhoea, impaired movement even to the extent of complete paralysis,

swollen stomachs and legs due to the enormous accumulation of water,

that is the human suffering here, the like of which beggars description.

Many howl with pain and abject misery under these hopeless conditions.

The fact that there is still a young British soldier who begs me shortly

before his death to tell his mother that he `died like a soldier'

testifies to the strength of spirit which exceeds all comprehension.

We have nowhere near enough ordinary bandaging material and we

experience increasing difficulties in treating innumerable tropical

ulcers, infected sores, fungal infections and skin lesions. We just have

available a little iodoform, a mixture of tooth powder, aspirin, boric

acid and ichthyol and also a little dermatol. The tropical ulcers have

gradually become so extensive that we have to admit men to hospital for

treatment. Then for a few days they can be tended with bandages soaked

in a solution of rivanol, chloramine or potassium permanganate. The only

salves, which we sometimes receive in the form of boric and ichthyol

ointments [used to treat skin complaints] are presumably made up in

unpurified lard so that when we use them eczema is often the result.

The doctors improvised. One 'concoction', used to coat ulcers, was made

from Japanese tooth powder, coconut oil and chalk. It formed a hard seal

but it was sometimes necessary to keep the patient off his feet. Surgery

was often then possible, using a deep incision near the ulcer to drain

off stagnant blood; borassic powder was used as an antiseptic. Some men

had to have this treatment ten times, but once the battle against

infection was won, recovery, as with appendicitis and war wounds, was

often rapid. Nonetheless, by 5 September, the death toll was 284.

But it was also in September that Mori finally authorised the building

of a bamboo jetty out to sea to serve as a latrine - a request first

made by Pitts when they had arrived four months earlier. The 'superloo'

was a major landmark in the history of Haruku, said Leslie

Audus: its effect on morale could not be overstressed:

'Compare the pleasure of squatting over gently lapping water and gazing

out over the blue sea to the beautiful, jungle-covered island of Ceram,

with the revulsion and misery of similarly squatting over a trench

filled with a stinging writhing soup of yellow faeces and fly maggots.'

Don Peacock was another satisfied customer: The opening of this

masterpiece was a great occasion for the Gunzo. He looked on with pride

as the first customers arrived and crouched on their haunches over the

holes like a troop of bare-bottomed monkeys. The British clutched

bunches of leaves; the more practical Dutch each carried a bottle of

water suspended from a finger with a piece of string. The Gunzo appeared

to consider for a moment these primitive Western ideas of hygiene, then

he strolled benignly along the line of squatting men presenting each

with a square of Nip toilet paper. As he stood back to see his gifts put

to good use, each man, British and Dutch alike, carefully folded up the

precious piece of paper and stowed it carefully away. The British used

their leaves, the Dutch their water. The Gunzo scratched his head and

walked away. Every scrap of paper on the camp, including even the odd

Bible, had been used to roll the local tobacco into cigarettes. Toilet

paper was certainly much too valuable to be used on backsides.

As Audus observed, if it hadn't been for the

'short-sighted bloodymindedness' of the Japanese, the dysentery epidemic

could have been averted and the airfield finished earlier.

The arrival of a party of mostly Dutch prisoners from Amahai in Ceram

in October had several effects on Haruku. It also had an effect on the

men from Amahai, who were shocked by what they saw, as one naval officer

recorded: When we came into the camp through the dank steaming jungle a

clammy fear gripped us. There was something indefinably cruel in all the

trees and climbing plants which grew over them ... threatening to engulf

the damp palm-frond huts of the camp to form a green hell. It was

forbidden for the healthy to go into the dysentery huts; a sort of

parody of a rule of hygiene, but one day a sailor came and asked me,

'Will you go to visit our big marine sergeant for a while? He would be

so happy to see you before he goes.' I slipped into the hut of the

`serious dysentery cases' and there, naked, lay a man I once knew as a

strong robust chap. Only the eyes were still alive. Maggots crawled over

the immeasurably befouled baleh-baleh [bamboo sleeping-platform] and

over his dying body. It was impossible for the two orderlies to clean

those Augean stables, and it was no use contemplating more orderlies.

Everyone had to go to the airfield. Mori took good care of that.

Overcoming their sense of shock, the Amahaiers determined to improve

the morale of the Haruku men. So they decided to work hard on the

airfield so that it was completed quickly, encouraging the Haruku men to

hold on in the hope of returning to Java. They sang and whistled as they

marched to the airfield and their attitude impressed the guards as well

as the Haruku old-stagers. The guards saw the work accelerating and

behaved somewhat more reasonably, said Audus, while

the original Haruku men felt themselves challenged and uplifted.

At the time of the Amahaiers' arrival the dysentery epidemic on Haruku

was largely over and the main killers were now the vitamindeficiency

diseases beri-beri and pellagra. Optical neuritis was also still causing

partial or even complete blindness. On 25 November a party of sick men,

'emaciated, naked and several unable to speak or see properly', and 'in

rags', left Haruku for Java. The Japanese had at last taken notice of

Pitts's appeals to evacuate them from the island. They travelled to

Ambon, where many were transferred to the 4600-ton Suez Maru,

which sailed on 25 November with about 550 British and Dutch prisoners

from Haruku and Ambon. Four days later the American submarine Bone

Fish torpedoed the ship. Seven Japanese were rescued; everyone

else died, some machine-gunned in the sea by an escorting Japanese

corvette. Another 280 sick Haruku men, who sailed the same day, arrived

in Java on 21 December. Twenty died on the journey.

Meanwhile, the arrival of the Amahaiers with their determination to

work had spurred Mori to improve the camp. New roads with storm gullies,

new huts, a parade ground, a new hospital with three wards, and a parade

ground were built by officers and men classified as 'sick-in-quarters'.

Nursing became easier. The men were also allowed to build fires in their

huts and could cook food. There were about eight acres of gardens which

grew tomatoes, maize, katella (manioc), sweet potatoes, lambok and other

vegetables. The Japanese took the vegetables; the men were given the

katella leaves. The men also dug a 20-foot well which then had to be

lined with stones and boulders brought back from every visit to the

river. If they failed to bring a load back, they were made to return and

as a punishment to hold the boulder over their heads. ....

By mid-January 1944, there was no more dysentery and only one or two

men were now dying each week. However, on 5 May, a year and a day after

their arrival on Haruku, the bombers were the only 'bringers of hope', said

Audus. There had been no fruit or fish in the shop for a week

and avitaminosis was increasing again. There were no medicines. Most of

the men wore only a Jap-happy. ...

During their first five months on Haruku 334 men died. After the

seriously ill men left, the sea latrine was constructed, yeast was

produced (using the techniques described in Chapter 18) and the gardens

started, 'only' 52 died in the last nine months. If only the Japanese

had listened. Haruku was gradually closed down in July and August 1944.

As the prisoners left the camp, beside the road, hidden in the bushes in

the half light, the local population of Haruku had turned out and were

playing a tune on bamboo pipes. It was the tune to When this bloody

war is over / Oh! How happy I shall be.

Leslie Audus recalled the scene: One will never know

whether they chose this tune because of the singularly appropriate words

or whether it was a happy chance because the tune is also that of the

delightful Salvation Army hymn, Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam

and they had clearly been visited by Dutch missionaries. As they

understood almost no English, it is probable that it was a happy

accident, possibly the happiest accident of a lifetime. Or perhaps -

engaging thought - they had heard the men singing it as they marched to

work and thought we went to work singing hymns. It was clearly an act of

sympathy, of solidarity, because they too had had their share of

maltreatment by the Japanese. It was a touching and moving experience.

The last party of half a dozen men, commanded by Audus,

departed for Ambon on 1 August, and the gate of the Haruku camp was

closed for ever. Had all the sweat, pain, beatings and death been in

vain? Audus wondered after the war. It was unlikely that the airfield

played any significant role in the Japanese war effort.

15 Sep 20 Geoffrey

Glover writes: I found this page yesterday when I was checking on the

internet about Professor Leslie Audus. He was my father's best friend

[from SGS days together] and they kept in touch until my father died on

May 28th 1987, aged 76.

I have the original framed photograph that you have as Late 20s School

Photo. I assume my father and Leslie Audus visited Soham in the mid

1980s and were given it. Unfortunately there is no date on it. On

part 5/9, Row 3, no.3 is my father Albert John Glover, and no.4 is Leslie

John Audus.

They were both at Cambridge together - my Dad went to Fitzwilliam while

Leslie was at Downing. We used to see them annually. My family stayed in

touch with him after my Dad died and I last saw him at his 80th birthday

party (1991). He stopped writing to us some years later after, I assume,

his eyesight deteriorated to the extent it was no longer possible to see.

Unfortunately we lost touch then as he must have moved and his family did

not stay in contact. In fact I only found out he had died when I looked

him up a few years afterwards.

I know my mother wrote to Soham Grammar School when my father died. It had

changed name by then but someone did write back to her with condolences.

[Soham Grammar School Admission Register 1922-1926

School Year 1922-23: 406 Albert John Glover

Leslie Audus is not listed - perhaps he entered SGS in the School Year

1921-22, before this volume of the Register.]

Sources: the Internet, Who's Who, The

Soham Grammarian, The Times, The Daily Telegraph, FE POW

Association, The Java Club, BBC, Brian MacArthur

If you can add to this page or correct it, please contact the editor web@sohamgrammar.org.uk

page last updated 23 Jun 12: 17 Sep 20