CharactersLEONTES, King of Sicilia - GD Rouse HERMIONE, Queen to Leontes - FW

Haslam TIME, as Chorus - REG Hood |

The

action takes place at the Sicilian Court and in the

Bohemian country-side. The play produced by Mr GE Hemmings assisted by Mr GEA Hammond Settings and costumes designed by Mr PJ Askem Set Construction - Mr RGS Bozeat Lighting - Mr G Parrott, Mr RJH Makin, Mr PD Scott Stage Management - Mr JW Rennison Make-up - WAG Burroughs Music Supervision - Mr MJ Ades Business Management - Mr CJ Ford, Mr LR Hart and Mr SR Saunders The dance in Act

IV arranged by Mrs E Stokes We wish to thank most sincerely the

parents and friends who have made the costumes; the

boys who have worked behind the scenes; and the many

other helpers within the School who have made an

indispensable contribution to the production. This

year, our thanks are particularly due to:- source : Frank Haslam (also photos) |

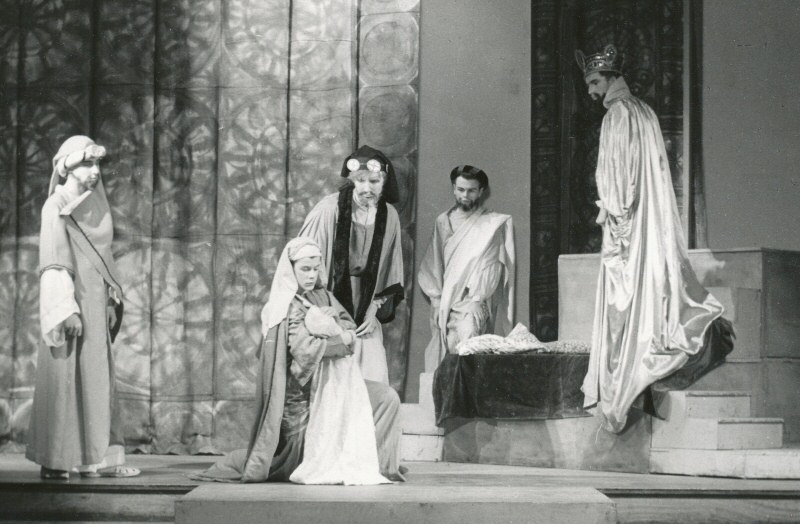

possibly ACT I Sc 2

Michael Page - Howie Docherty - M Rogers - Geoff

Rouse - L Covell - Frank Haslam (source: Haslam)

ACT II Sc 2 A court of Justice

Malcolm Coe - John Chapman - 3 - Alan Christie -

Frank Haslam - T Reynolds - 7 - 8 - Clive Taylor - 10 - Geoff

Rouse - Michael Fitch - G Ball - David Register (source:

Haslam)

Act II Scene 3 A room in Leontes' palace

G Ball - Alan Christie - Anthony Butler - Michael

Fitch - Geoff Rouse (source: Rouse)

Act IV Scene 4: Sheep Shearing

1 - 2 - 3 - Andrew Bailey - G Pollard - 6 - TC

Salmon - Peter Aves - 9 - 10 - 11 - 12 - 13

(source: Rouse)

Act V Leontes (Geoff Rouse)

(source: Rouse)

Act V - as in the Spring 1963 Soham Grammarian

L-R: Clown - Autolycus - Old Shepherd - Paulina -

Perdita - Hermione - Leontes - Polixenes - Camillo - Florizel

- ? - ? - ? - ?

Identifications: Haslam, Hemmings

THE WINTER'S TALE

from the Spring 1963 Soham Grammarian

The Winter's Tale for a school production? This does not seem to many, perhaps, an obvious choice. This is a play not often performed, comparatively little known how many in the staff-room, for example, could say that they had read or seen the play before? A play strangely neglected: at least this would be, assuredly, the opinion of all those who saw the production by Mr. Hemmings at the school this year. For if the choice did not seem 'obvious', the results were a triumphant vindication. Rarely could one have seen a more satisfying school performance of any play.

Intelligence seemed the keynote of all the acting. Every boy seemed to understand his part fully, and this understanding was conveyed in the clarity of the diction and the accuracy of the phrasing. Some of the credit for this must go to Mr. Hammond, who spent much time training individual actors in their parts and ensuring that they grasped the sense of their words. Behind Rouse's excellent performance as Leontes seemed to be a mind constantly alert, thinking through and living the part. Rogers as Polixenes made excellent use of the resonance and range of his voice, bearing himself with dignity and appropriate hauteur. Haslam made an exquisite Hermione, and in the statue scene, so touching in its gentleness and mystery, played with well-balanced restraint. Nor were the comics without their successes: Aves as Autolycus was an accomplished rogue, overcoming the difficulties of the part with remarkable skill, and Dean and Green, as the Old Shepherd and Clown respectively, seemed made for their parts. Pollard, with his clear voice and charm was an engaging Florizel, balanced by a demure Bailey as Perdita. Christie as Paulina earned the praise of the Headmaster for his rendering of the scourge of the erring Leontes. Excellent support was given to all of these by Page as Camillo, Docherty as Archidamus, Covell as Mamillius, and Butler as Antigonus, until the latter was chased by Starling, disguised as a Bear.

We must not overlook, indeed how could we, the superb costumes and stage designs of Mr. Askem and Mr. Bozeat. Part of our pleasure was in the spectacle these beautiful and highly original costumes constantly provided.

This is a performance that we shall all long remember and which will become the standard by which other future productions will have to be judged.

source: Stephen Martin

Gordon Hemmings, the Producer, wrote an article The Play Produced: The Winter's Tale, intended for publication in an educational magazine "but it never saw the light of day". It provides a fascinating insight into the background to this particular production. Those taught by Gordon may be amused to note that the editor transcribed his 2150 word handwritten article ... and so is responsible for any errors ...

![]()

'The Play Produced: The Winter's Tale' - an unpublished article by Gordon E Hemmings

'A sad tale's best for winter'. So I decided in July as I searched for a Christmas play for our two-stream boys' Grammar School on the edge of the Fens. We had previously performed two predictable favourites, The Dream and Twelfth Night; we had no tragic hero in the School but a number of promising actors at all levels; and as I am very fond of the Last Plays The Winter's Tale seemed a good if challenging choice. You will notice that I have assumed that the chosen play would be by Shakespeare; while remaining this side of bardolatry, I am convinced, like many other teachers of English, that Shakespearean drama - or to be less bardolatrous, Elizabethan & Jacobean drama - offers ideal material to a cast of boys.

Soon after the play had been chosen, and after I had made sure that I could fill the eleven main parts (from Leontes to Antigonus) adequately, several of the staff and the Sixth Formers most closely connected with the production spent a few days at Stratford, where we saw The Dream, Macbeth and Cymbeline. Although we had some reservations about the details of these productions, there is no doubt that we were all inspired by this visit to try and make our own production as perfect as possible - always remembering that our first responsibility throughout the coming term would still be to teach and to learn.

In our early discussions about the set, it seemed natural that the designer (our Art Master) and I should decide on the simplest of basic sets, rejecting the idea of a front curtain, and throwing out an apron stage towards the audience, in the now familiar Stratford manner. On stage left we planned an elaborate arrangement of levels and connecting steps, rising to a height of about five feet, and to balance this on stage right - though set further back - an erection which was variously christened the bird cage, the pagoda, the temple or the gazebo, according to mood. Six slender double columns supported a vaulted roof, though with only two ribs actually showing: this began as quite an elaborately decorated object, but when we eventually saw it in position on stage, we cancelled all further additions to it and were very happy with its graceful silhouette, interesting from all angles. Scene changes were to be made in front of the audience by uniformed attendants, who drew tapestries to conceal the bird-cage and to vary the backing behind the levels to suggest interior or exterior settings. Originally we had hoped to drop down these tapestries from above, but lack of height above our stage made this idea impracticable, and we were finally much better pleased with the forced alternative. As often in school productions, apparent limitations can prove unsuspected assets.

I was very anxious to emphasise the fantastic 'old tale' elements of the play, and we decided to dress it in a freely interpreted fairy-tale-Byzantine style, and to make liberal use of music. We are very fortunate in having the tradition of designing and making our own costumes: the designer's first sketches assured me that he had caught exactly the right contrast between the almost barbaric splendour of the Sicilian court and the gentle, but not too pretty, pastoral world of Bohemia. And so throughout the term these sketches were excitingly turned into real costumes by mothers of the cast and friends of the School; many of the details - brooches, painted panels and so on - were made by the boys themselves. By concentrating on achieving variety of texture with such materials as were available the designer was able to work on a comparatively limited range of colours: gold and browns in the Sicilian half of the play, with the addition of greens and yellows when Bohemia was reached, with a mourning court in greys and purples for the return to Sicilia.

This same emphasis on contrast within a basic unity was captured in the music of the play, which was used not only to cover scene-changes and create atmosphere but also sparingly behind the actual speeches - for example, we had an oracle theme, which we used whenever the oracle was mentioned. Most of the music came from Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra, which supplied us with themes passionate, supernatural, comical-pastoral, pastoral-lyrical - and even the tunes for Autolycus to sing. We also used the same composer's Violin Concerto and Rumanian Dances, and - most effectively - two of Britten's Sea Interludes, one of which gave us a splendid storm and 'Exit Pursued by Bear', and the other a moving dirge.

But the actors bear most of the burden in a Shakespeare play, and no matter how effective the other details of the production, they alone can bring the play to full life. I first realised that I had a potential Leontes when I heard a Sixth Former who had played a lively Quince and Fabian for me win our Speech Contest with a surprisingly moving performance of a poem by Sidney Keyes and a passage from Revelation. For the three Old Men's parts I had to rely on largely untried material, but in the event we managed to produce a splendidly intelligent Camillo - what a thankless part this can be! - a subtly comic old Shepherd, and a firmly honest Antigonus. I had two remarkable strokes of luck with Polixenes and the Clown: the boys I had provisionally cast in these parts both withdrew from the cast at the beginning of term - one through pressure of work, the other through leaving the district - but the two substitutes, promoted from a Lord and a Servant, eventually proved perfect choices.

Last year we had broken the Shakespearean tradition to do a double-bill, one half of which was Menotti's Amahl & the Night Visitors; and from the cast of this I found my Autolycus, who added an unsuspected urgency to his excellent voice, and Hermione and Paulina, who had shared the part of the Mother in the Menotti opera, and whose voices were now exactly at the right stage for these two key parts. Olivia had matured into a handsome and poetic Florizel, but the search for Perdita was long and difficult; for the first few weeks of term, she was in a very real sense "the lost one". At last, I decided to put my trust in a Third Form boy who had been one of the two Amahls. And so, with plenty of enthusiastic Middle School boys and some pressed Sixth Formers (many of our country-boys tend to hide lights under bushels until almost too late) to fill out the large cast, the initial process of casting was complete.

One main difficulty in producing Shakespeare with a young cast is to ensure that every actor knows the meaning of every line he speaks. The text of The Winter's Tale is one of the most difficult in the canon: we used the Penguin edition, which has some rather unhelpful 'original' punctuation, with frequent help from the New Clarendon, which we had used for two years at A level. I had invaluable assistance at this stage from one of my colleagues who undertook much of the spade-work of ensuring, within the limits of their age and intelligence, that every member of the cast understood what he spoke. This enabled me to concentrate on movement and action almost from the first weeks of term; rehearsal time is especially precious in a country school such as ours, where life tends to stop at 3.50 p.m. (when the school buses leave) and where transport problems for boys living anything up to fifteen miles from school create extra worry. Fortunately, my Leontes was one of the handful of Soham boys in the school, and therefore on the spot; Florizel was similarly well-placed, and Polixenes one of our few boarders. The rest of the main characters endured cheerfully the inconvenience of an infrequent bus service: even so, few rehearsals could extend beyond 5.15 p.m., and every brief lunch-break had to be used.

Our set worked well from the start: the extra apron-stage was excellent for establishing actor-audience relationships in such passages as Leontes' jealous asides, Antigonus' arrival in Bohemia, and Autolycus' intimate monologues. The arrangement of levels and steps made interesting and significant grouping possible, and was especially useful in giving Leontes authority in the Trial Scene and the tyrannical passages generally. And we used the bird cage for the dumb-show exchanges between Polixenes and Hermione in Act One, for the entrance to the Prison, for the Shepherd's Cottage (suitably ivied) and for the statue of Hermione in the last scene.

The scenes which gave us the greatest difficulty in rehearsal were the immensely long opening Act, and the even longer Sheep-Shearing Feast, and the last scene. I tried to enliven the opening conversations between Camillo and Archidamus by allowing the main characters to enter more or less as they were mentioned in the dialogue, thus gaining a somewhat ironic effect similar to that at the opening of Antony and Cleopatra. This worked well, especially when the royal actors were enriched by their magnificent golden robes and crowns. The two Kings and Hermione were, not unnaturally, rather slow to catch the very elaborate courtly ritual of their opening speeches, and the first overt disclosure of Leontes' jealousy was always a difficult moment.

Eventually, Leontes decided to take a hint from Neville Coghill, and play to suggest coolness, if not quite suspicion, from the very beginning; this seemed to help the scene enormously, and the make-believe of costume and make-up allowed final reserve to be thrown away, and the violent emotions of the play to emerge in all their frightening power. I find the other great problem with Shakespeare, the achieving of that 'larger-than-life' quality of speech and movement so essential to poetic drama, is only fully possible for many of these schoolboy actors when every detail of the actual performance is there. Then even the producer can expect to be surprised - and thrilled!

The Sheep-Shearing Feast poses great problems of pace and organisation. The welding of the individual 'paragraphs' into a satisfactory essay long eluded us: Florizel and Perdita dallied and danced charmingly (co-operation here from a Drama Mistress in a neighbouring school); Polixenes raged eloquently; Autolycus teased the rustics engagingly - but still the scene as a whole tended to drag. Perhaps only professional timing can keep the scene moving without obscuring the intricacies of the plot or accelerating the tedium of old age. At least we retained clarity and the attention of the audience to the last.

The final scene of the play is in many ways the most difficult to stage: the statue cannot be placed too far forward, or the illusion is lost and the effect of the drawn curtain difficult to manage. In practice, we had to place Hermione in the gazebo, where on a low pedestal and veiled in white she made a most imposing picture; but the manoeuvres which are necessary to avoid too much speaking back and masking are a real problem - I should dearly have liked to have seen Shakespeare's original production of this scene; perhaps Hotson's theories would be triumphantly justified! Schoolboys find it difficult to suggest the change from early to late middle age suggested by the gap of sixteen years, and Leontes and Paulina were well advised to concentrate on suggesting old, rather than late middle age, and this development they both movingly managed.

The magic of the statue which comes to life worked with our audiences; their audible gasp, as a radiant bride-like Hermione moved to reunion with her husband triumphantly justified Shakespeare's boldest coup. But even then remains the problem of the last speech and the clearing of the stage: no impressive tableau for a production which uses no front curtains. Again, the audience helped by greeting delightedly Camillo's assignment to Paulina, and we tried for a solemn yet happy final procession, with banners leading off the main pairs of characters. Disposal of the standers-by proved awkward until - I think it was as late as the first Dress-Rehearsal - I had the idea of letting Autolycus remain on-stage fractionally after the others had gone, scratching his head in puzzled admiration over the vacant pedestal: this worked.

My final anxiety was over the length of the production; despite tactful cutting (not bowdlerising, I hasten to add) the play ran for 3¼ hours. Had we been too leisurely in our careful exposition of the text? The audience's absorbed attention to the very end gave us our answer. The most rewarding praise was to hear from many of them: "I hadn't seen this play before, I don't generally like Shakespeare but I was surprised to find that I could understand it all." Unexpected enjoyment is a welcome reward for hard work.