| I'd

like to first of all thank Frank Haslam for inviting me to

give this talk. I hope it will be interesting. I've tried to

make it a mix of some anecdotes about my early life at Soham

and some short account of my career in the pharmaceutical

industry for more than 50 years. I've also tried to set that against a backdrop of what was happening in the world of biotechnology throughout my life, throughout many of our lives. Because that has been an astounding story of science and development, especially in the medical field. I'm very honoured to be asked to give this talk in view of all the distinguished people that have given talks in the past. |

|

|

My career has really been

a fantastic journey, combining science and business.

But at the bottom of it all, Soham Grammar School was really foundational to this success, especially the the training that I got in science. |

|

| So

why did I call this From Soham to the Medicine Chest of

the World? Well, New Jersey is known as the Medicine Chest of the World because it has grown up over 150 years to be the home to more than 300 biotechnology and 20 pharmaceutical and medical technology companies. Most of the world's top 20 firms have major facilities there. And more than 150,000 highly qualified people live there and work in this industry. So it's a very dynamic environment for this this type of work. |

|

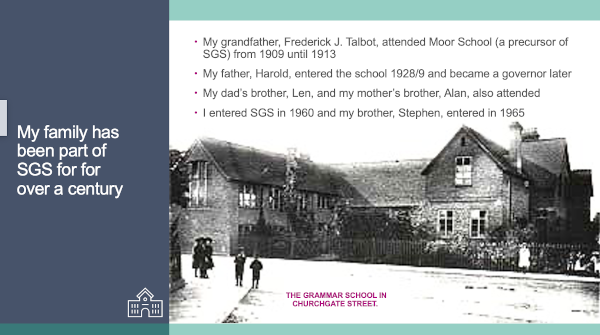

| My

family has been part of Soham Grammar School for over a

century. The first member who attended was my grandfather,

Frederick J Talbot, who was mentioned at our Reunion by Phil

Green, and I'll come back to that. Fred Talbot attended the Soham Moor [Endowed] School, the precursor to Soham Grammar School, from 1909 until 1913. You can see a picture of the old school building in Churchgate Street. My Dad, Harold, attended the school - I'm not exactly sure year he entered, 1928 or 1929. Later on he became a Governor, representing parents. |

|

I entered in 1960, and Stephen, my brother entered in 1965.

I was born in 1949 and lived my early few years in Soham, then the family moved to Ely in 1953.

|

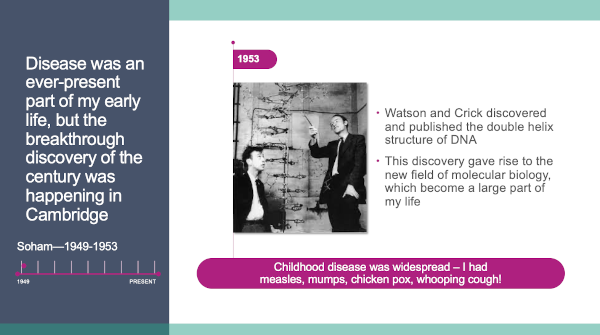

This was a really amazing time in science because in that

year, 1953, Watson and Crick working at the University of

Cambridge, just down the road, discovered and published the

double helix structure of DNA. This had been a goal of scientists for decades and many people contributed to it, but they finally put the pieces of the puzzle together and published a one-page paper in 1953. With this structure, for which they won the Nobel Prize, this discovery gave rise to the new field of Molecular Biology, also known as Biotechnology. This became a large part of my life. |

|

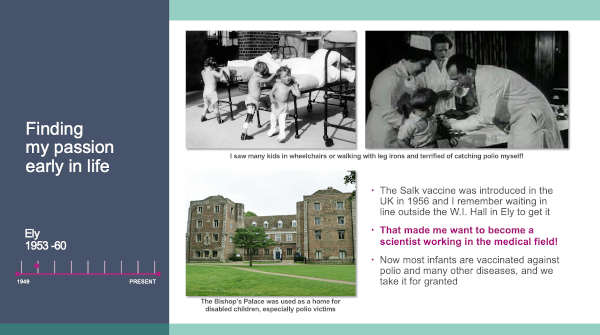

| As

a child I remember that disease was widespread. I myself had

measles, mumps, chickenpox, whooping cough and other

diseases. Living in Ely as a 5-7 year old child, I particularly remember that in the High Street you could see young kids in wheelchairs or walking with leg irons because they had caught polio, an infectious disease. The Bishop's Palace on the Palace Green near the Cathedral was used as a home for disabled kids, especially polio victims. These kids were out being shown around, getting the air in Ely. I remember seeing this and being terrified of it. |

|

I thought this was just an absolute miracle that I'm not going to get this disease.

Now most infants are vaccinated

at birth and regularly throughout their early years against polio

and many other diseases.

We take it for granted these days.

It's hard to explain, especially today, when so many people are

unwilling or refusing to take the COVID vaccine.

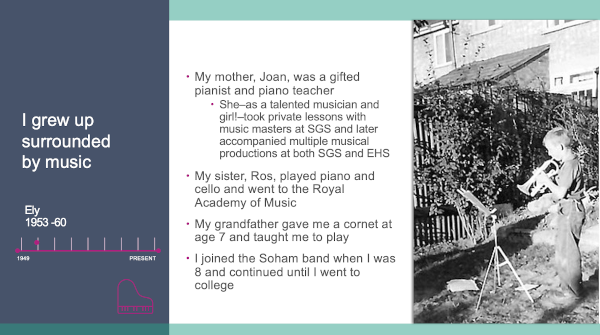

| I

grew up surrounded by music, the house was always full of

music. Maybe some of you remember my mother, Joan. She was a

gifted pianist and a piano teacher for many decades. She'd had no formal music education. Girls didn't go to college then and there happened to be a war on, but she took private lessons with some of the music masters at Soham Grammar School. Later on, she accompanied many musical productions at both SGS and Ely High School. My oldest sister Ros played the piano and the cello, and she went to the Royal Academy of Music. |

|

I joined the Soham Band when I was eight years old and I continued being a member until I went to university in 1967.

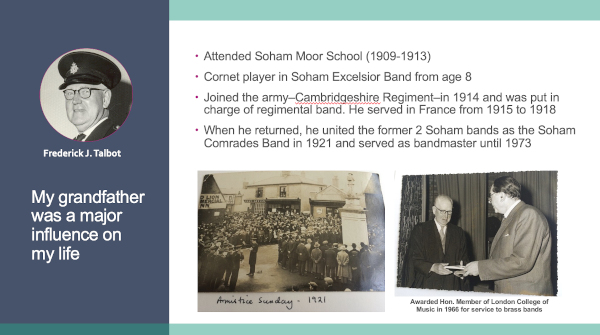

| My

granddad was a major influence on my life, both for the

music but also in general. As I said, he went to SGS. He had

been a cornet player in the Soham Excelsior Band from the

age of eight, prior to WW1. In 1914, after war broke out, he joined the Army. Because of his cornet playing he was put in charge of the Regimental Band - incredible, because he was very young, in his late teens. He served in France from 1915 to 1918. I tried to track down exactly where he was but I couldn't really find out anything. |

|

In the old picture from Armistice Sunday 1921, a 100 years ago, you can see my grandfather conducting the band. On the ground behind him is his cornet on which he was going play the Last Post and Reveille in memory of the Fallen. This became a tradition at SGS. Many of you must remember the Remembrance Services at school. I played the Last Post and Reveille for several years in that service. My granddad coached me on how to play them properly.

On the right you can see in 1966 him receiving an Honorary Membership of the London College of Music for his services to brass bands. It is being presented by William Lloyd Webber - you may have heard the name Lloyd Webber. He was the father of Andrew Lloyd Webber, the famous composer of musicals, and of Julian Lloyd Webber, the famous cellist. At that time Lloyd Webber was the Director of the London College of Music.

|

So with all this musical background, and some interest on my

part, I was really torn about which way my career should

develop. Should I pursue Science, which was very interesting - I mentioned the Salk vaccine story? Or should I go into Music and follow my sister to college. Brian Halls [SG55] was a trumpet player who won a place at the Royal Academy of Music. I thought, well, if he can do it, I can. But I still couldn't make up my mind what what to do and what A Levels to do. After many discussions I opted to do Chemistry, Physics and Maths, having been told that if I wanted to do Music, I could still do it after A Levels. |

|

| Ely

at that time was a very musical city. There was the

Cathedral Choir singing every day in the Cathedral. The

King's School had a very strong music tradition. And of

course Ely was very close to Cambridge, which was a musical

city. There was a thriving amateur music scene in Ely and the annual Ely Music Festival. My arch rival in the recorder section was Eric Pearson [SG60], now in Kuujjuaq, Canada. There was a strong Ely Choral Society under the direction of Hilary Dewar [EHS Music until 1967]. They staged several magnificent concerts in the Cathedral. Peter Scott, who I think was a member, could confirm that that was a very thriving society. |

|

Hilary Dewar also put together an

orchestra of local musicians for these concerts. This

included my mother, plus members of the Cambridge Music Society.

Brian Halls and I made up the trumpet section. I also played in

the County Youth Orchestra in Cambridge, where we practiced and

gave concerts in the Corn Exchange on the Market Place.

I had quite a lot of contact with

the King's Ely boys. One was a very brilliant flute player, but he

had to give it up because he had asthma. He took up the cello

instead. He told me once "Well, that maybe very interesting, that

Science, Michael, but you'll get more reward out of going into

Music." He became a professional cellist in a London

orchestra.

| I

talked several times to Ted Armitage about this and he said

"Well, Michael, from what I've seen, you're a good

scientist." Nobody had ever talked to me like that before. He went on "If you take my advice, you will follow the science and keep music as a hobby." And I realised that I would only be able to become a scientist if I studied science. So the outcome was I followed the Science. |

|

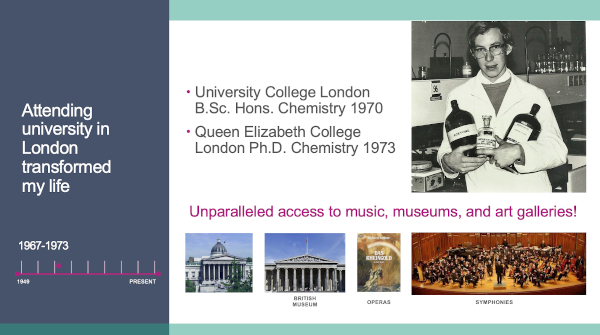

| I

went to University College London [UCL,

on the left], as Frank has already mentioned. I got a degree in Chemistry in 1970 and followed that with a PhD in Chemistry in 1973. Apart from attending college in London, I also loved the access to all the culture, the museums, the opera houses, and the symphonies. This was kind of a good compromise for me. |

|

|

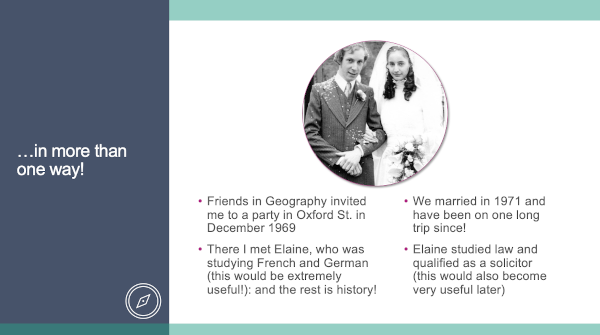

Geography got into my life and affected me more than one

way. I had good friends in the Geography Department and they invited me to a party in Oxford Street in December 1969. And there I met Elaine, who was studying French and German at UCL (which would turn out to be very useful) and the rest is history. We got married in 1971. And we have been on one long trip since. After UCL, Elaine studied Law and qualified as a solicitor (this would also become very useful later on). |

|

There was a recession on, there was double-digit inflation.

There was the oil shock, rationing of fuel and other things.

This was a tough time to get a job.

| But

somehow I managed it. My first job was as a research chemist

for Hoechst AG, one of the big German chemical companies.

They had just built a new lab in Milton Keynes, where I went

to work in drug discovery and early drug development for

seven years. Hoechst was the number one company in pharmaceuticals at that time. It offered a lot of opportunity. I liked working in the lab. It was very exciting, making new compounds and and testing them for biological activity. |

|

And so Elaine and I packed our bags and went to Germany.

| I

went out in June 1981. It was a tough beginning, I couldn't

speak the language! I took one-on-one German lessons for three, four hours in the mornings, which was very tiring. And then I went to the office in the afternoon. Elaine followed in September 1981, seven months pregnant. We did a crash course in birthing and parenting together in German with a lot of long words, which I won't even try to pronounce in this talk. I was very thankful for Elaine's linguistic fluency in German. |

|

We spent Christmas as a new family in Germany, and celebrated the New Year in German style, with Sekt sparkling wine and fireworks in the street.

Our son Christopher was also born in Germany, in 1983.

| My

first job in Germany was in global clinical development. I'm

not a medical doctor, as someone mentioned earlier, but

Hoechst was developing drugs all over the world. They had a

network of about 30 medical departments in major countries

around the globe. All of that activity needed to be planned

and managed. My initial role was to try to streamline the clinical development and regulatory approval process across the major countries. This meant changing the model from the one they'd been using where the first goal was to get approval in Germany and then worry about the rest of the world later. It was leading to huge delays in getting drugs on the market in the US and other countries. |

|

I proposed a way to speed up development, and also that clinical development programmes should be planned globally from the beginning.

| We

started what we called International Project Groups, with

members from key countries sitting together around the table

or in those days communicating by fax or phone as there was

no email then. We started to implement that in 1986 and it was a great success. |

|

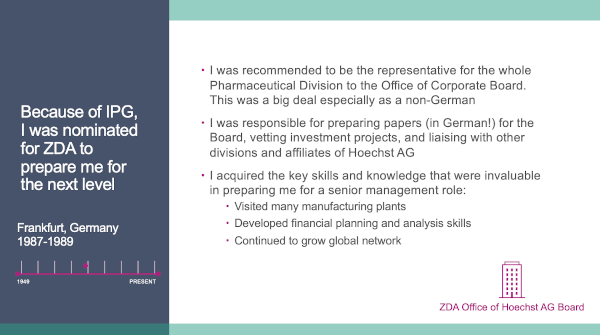

| Because

of that I was recommended to become a member of the Office

of the Corporate Board that reported to the Board Chairman.

This was a big deal, especially since I was not German. My job consisted of preparing briefing papers for the Board on pharmaceutical matters, vetting investment projects and doing liaison work with other business divisions and affiliates of Hoechst around the world. |

|

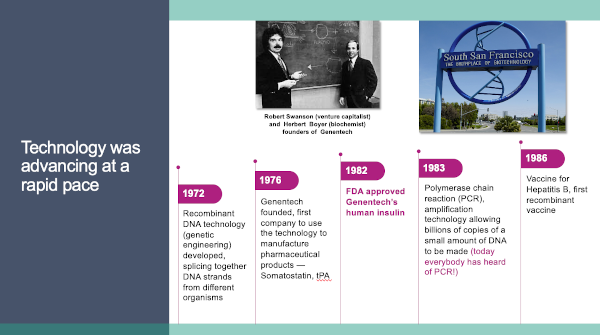

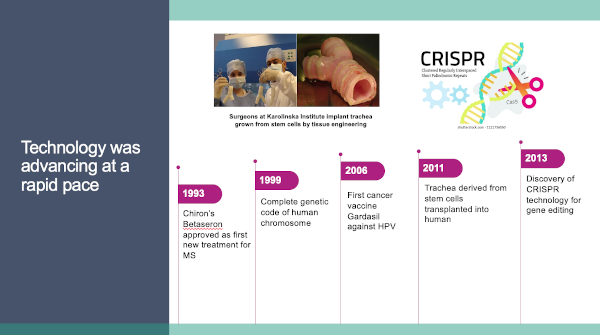

Here's a quick thumbnail of what was taking place in the biotechnology field during those years.

|

A big breakthrough came

based on the Watson and Crick work in the 1950s -

recombinant DNA technology was invented and developed in

1972. This was finding methods to splice together the DNA

strands from different organisms and then using that to

grow and produce medicines on an industrial scale.

In 1976 Genentech was

founded, the first company to use the technology to

manufacture pharmaceutical products, such as Somatostatin

hormone, or tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) which is a

compound for dissolving blood clots after thrombosis.

|

|

In 1983, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was invented. This is an amplification technology, allowing billions of copies of a small amount of DNA to be made and analysed.

Today everybody has heard of PCR because of the COVID test. And in 1986, the first recombinant vaccine came to the market for Hepatitis B infections.

| My

next career step was business development. I joined

Hoechst's Business Development and Licensing department in

1989, it was then just three or four people. I was responsible for the United States territory. I said "What do you mean? Companies, academia, biotechnology?" They said "Oh, everything." So this got me involved in frequent travel to the US. |

|

| But

what is business development? Well, simply put, it's the creation of partnerships with other companies to enhance the growth and profitability of the business. And it can cover multiple areas of the industry, from research collaborations, through technology and product licenses. It can be in manufacturing. There can be joint ventures between companies, mergers and acquisitions, or it can be co-development or co-commercialization alliances. |

|

Even the biggest companies can't spend enough money and hire enough scientists to make all of the important discoveries. It gives access to funding for small companies, it's a way of cost and risk sharing. It's a way of accessing development expertise in certain specialist areas. It can give you access to sales or marketing or distribution channels. It can help you shorten development times and extend product life cycles.

So how do you actually go about that? There's really only one way to do it. Because drug development is such a complicated and multifaceted activity you need cross-functional teams, combining experts from research and development, marketing and sales, legal, patent, and manufacturing and regulatory affairs. The business development manager leads and manages the team. So it's a really interesting role because you're seeing projects and the company working together as a whole.

|

A century ago this year,

Frederick Banting, working at the University of Toronto,

discovered insulin and, together with Charles Best,

developed a process to extract it from pig pancreas, which

they patented.

Banting showed that insulin could be used for the treatment of diabetes. For this work he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine. The patents were sold to the University of Toronto for a nominal $1. The university subsequently licensed the technology to several companies around the world, including Hoechst, to make insulin available to diabetic patients. |

|

| In

my 25 years in business development in the industry I worked

on and was responsible for more than 100 deals. These are some of my favourite deals. The two in red, I'll talk about in more detail, but they covered the time period from 1992 to 2010. It covered many different areas of technology and medicine. |

|

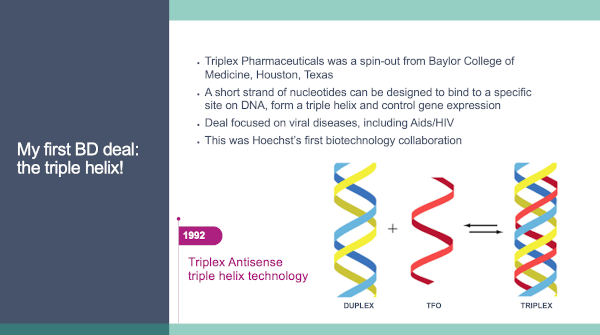

| The

very first deal I did was with a company called Triplex

Pharmaceuticals, which was a spin-out from the Baylor

College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. I talked earlier about the double helix, that Watson and Crick discovered in 1953. Triplex was trying to develop a triple helix technology. This involves taking short strands of nucleotides - this is the material that the DNA is made up of - and using the third strand to bind to the double helix and block certain parts of the genetic code. The gene expression arising from this collaboration was focused on viral diseases. We were very interested in those days in the AIDS HIV area. |

|

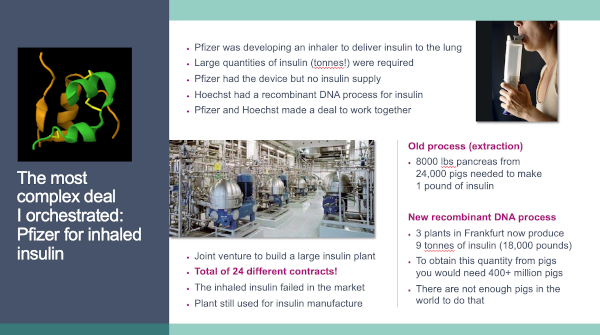

| The

most complex deal I ever orchestrated was Pfizer for inhaled

insulin. This is the company that now has one of the COVID

vaccines. You can see the structure of insulin in the box on

the left of the slide as two strands of peptides [brown and

green] linked by disulphide bridges [yellow]. Pfizer in the mid 1990s was developing an inhaler to deliver insulin to the lung. This administration route is a way of raising the insulin levels very rapidly and controlling blood sugar in a very rapid fashion. The disadvantage of this approach is that you need large quantities of insulin, tons of it, because it's not a very efficient route. |

|

Unfortunately the inhaled insulin failed in the market. For some reason, despite all the market research that had been done, patients didn't want to use it, and doctors didn't want to prescribe it. So it was withdrawn from the market.

But the plant that was built then is still used for making insulin. In fact two more similar plants have been built since. The old way of making insulin was to extract it from the pancreas of pigs. It's a pretty messy process as you can imagine. You need thousands of pig pancreases to get one pound of insulin.

With the new recombinant DNA process the three plants in Frankfurt are now producing nine [US] tons of insulin a year, that's 18,000 pounds. To get that much insulin from pigs you would need 400 million pigs - there just aren't enough pigs in the world to do that.

And keep in mind that there's two other companies that make insulin, Eli Lilly in the USA and Novo Nordisk of Denmark - these three companies between them are making something like 50 tons of insulin a year.

| I

stayed in Business Development. The companies changed but

the groups got bigger. In 2000 to 2004 [with Aventis] I

ended up with something like 60 business development staff

at corporate sites in the US, France, Germany and Japan, and

local groups in key countries in Europe, Latin America,

Southeast Asia, and so on. We completed many partnering

deals across the globe. In 2004 Aventis itself was acquired by Sanofi of France. It's now just known as Sanofi. I left the company and I joined a Canadian company called Biovail Corporation, headquartered Toronto, Canada. I stayed in New Jersey, but frequently went to Canada on trips. |

|

| Now

we're going to catch up with the technology advances in the

next decade, 1993 to 2013. These of course, are just highlights. In 1993 a company called Chiron got Betaseron approved as the first new treatment for multiple sclerosis and this was made by genetic engineering. In 1999 the complete genetic sequence of the human chromosome was published. This had been an ongoing project on a global basis for about a decade. |

|

In the early 2000s the whole field of tissue engineering or re-engineering came up where you can grow pieces of skin or organs from stem cells. These are the basic cells that carry all the genetic information needed to make an organism.

And in 2011 as you can see in the slide, a trachea was grown from stem cells. This part of the respiratory system in the throat was transplanted into a human for the first time at the Karolinska Institute in in Stockholm, Sweden.

In 2013, there was another major breakthrough in technology with the discovery of CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats). This is a new and very powerful technique for gene editing which has made the whole process much, much faster and more powerful.

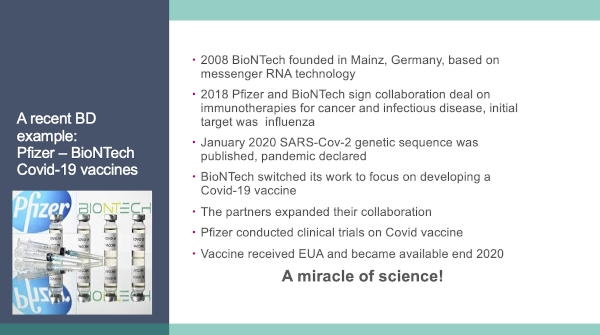

| In

2018 - this is before the COVID 19 virus was detected and

identified - Pfizer and BioNtech had already signed a

collaboration deal to develop new immunotherapies for cancer

and infectious disease and their initial target was

influenza. However, after the the SARS COVID sequence was published on January 19 2020 and the pandemic was declared, BioNtech switched its work to focus on developing a COVID-19 vaccine. The partners Pfizer and BioNtech expanded their collaboration to cover that, with BioNtech being responsible for creating the novel messenger RNA that would be used and manufacturing it. Pfizer was responsible for conducting the clinical trials. |

|

This and the simultaneous development of other vaccines such as the AstraZeneca vaccine, working in collaboration with Oxford University, and the Moderna vaccine and others - this is just a miracle of science how all this was achieved in such a short timeframe.

And it's just a measure of what can be done when people across the globe put their minds and their energy to work together.

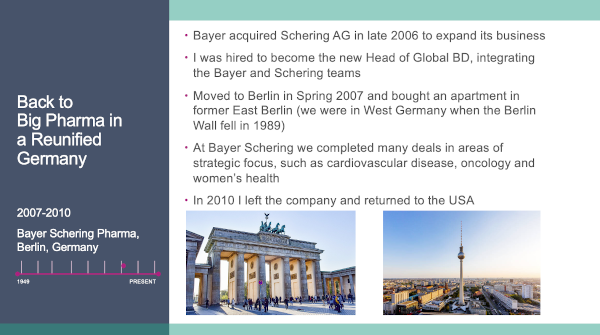

| Back

to my career, the final stop in Big Pharma. I joined Bayer of Germany after being in the US for almost 20 years. Bayer hired me at the end of 2006 to become their new Head of Global Business Development after they acquired Schering AG in late 2006. So Elaine and I moved to Berlin in the Spring of 2007. We bought an apartment right in the middle of the former East Berlin. This in itself was an amazing experience because Germany had been divided by the Wall for all the time we'd been in West Germany, until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. |

|

But by 2010, I was ready to move on.

| Elaine

and I went back to the US, in New Jersey, where we combined

our knowledge and expertise to found an independent

consulting company called Partners in Pharma. We've been doing that now for 11 years, offering independent advice and business development support to the global industry. Over the course of my career, and all those deals that I did, I got to know thousands of people across the global industry, and companies from Brazil, to Korea, to Japan to Australia, India and China. We use that large network of contacts to identify and create deals for companies which ask us for help. We can work from almost anywhere with a good internet and cell phone connection. |

|

We're still going but we're winding down.

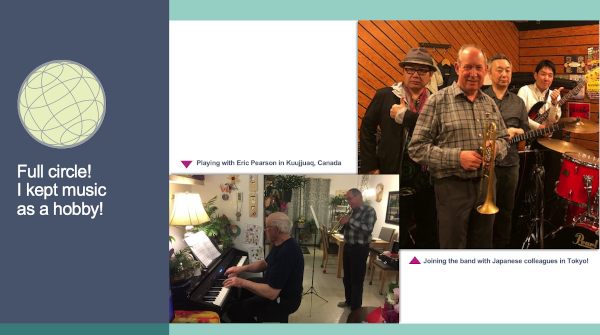

| This

has given me a bit more time. I've had time to pick up the trumpet again, after a break of 50 years. The photo on the left is with Eric Pearson in Kuujjuaq, Canada, as he mentioned. Three years ago, Elaine and I went up to visit and we were able to play again for the first time in 50 years. The other photo is me having a couple of sessions with Japanese colleagues playing in a jazz band in Tokyo. |

|

| So

coming full circle, at the end of the day, I hope I've been

able to make some small contribution to improving

healthcare, and improving the lives of patients across the

globe. None of this would have been possible without Soham Grammar School and the foundation that I received there, and all the people who helped me on my way after that. |

|

Coming back to SGS and a few of the staff members who particularly influenced me.

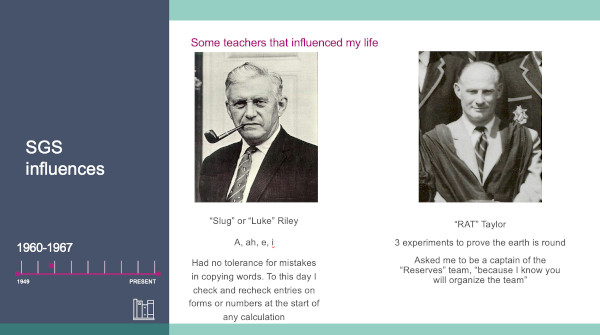

Slug/Luke Riley. I remember the first day, the first French lesson with him. He came into the room and he said "Open your books to the middle page and divide it into 16. I'm going to tell you all the sounds in French." We had to repeat this every time he came into the class A ah e i and all the rest. I remember that he had absolutely no tolerance for mistakes and copying words. If you didn't correctly copy a word you were in real trouble. And to this day, I check and recheck entries on the forms or numbers at the start of any calculation to make sure that the input is correct. I really put that down to his teaching. |

|

RAT Taylor has been mentioned a couple of times. I remember his first lessons in Geography - three experiments to prove the earth is round. (It was the little ship going over the horizon. That was the first one. You know, the way the ship disappears over the horizon, and then the funnel with the smoke is the last part to disappear.

The second one was the Bedford Levels experiment where you put posts into the ground. You knock them in to the same amount and then you look at the tops of them and they're not exactly aligned.

I'm forgetting the third one - maybe somebody can help out with that?)

Later on, I guess it was when I was in the Sixth Form, he asked me to be Captain of what was euphemistically known as 'The Reserves' team. These were the the boys who couldn't play football well enough to be in the First or Second XIs. We were more or less left to our own devices to organise ourselves to play some football. He said "I'm asking you to do this because I know that you can organise this team." And that was the very first experience I had of trying to organise or lead a team.

I always remember that because as my career progressed, I was in a position of leading and having to lead larger and larger and ever more complex teams. But I think it's the same set of skills that you need. It's communication. It's understanding, it's listening to people, the kind of soft skills that you need in business development to get deals done.

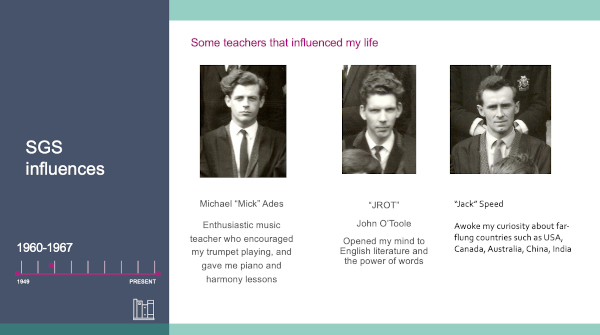

| Three

other characters here. I think some of you will recognise Michael Ades, the Music teacher [1960-66]. I think he was new to the school in 1960, the year I started. He encouraged my music greatly, my trumpet playing, and I took piano lessons with him and some harmony lessons. JROT - John O'Toole [English 1963-66]. I'm sorry that he is not able to join us at the last minute. He did join us last year and I was very happy to open up an email correspondence with him. I was able to remind him of a few of the lessons that he had given us, where he really opened my mind to English literature and the power of words. |

|

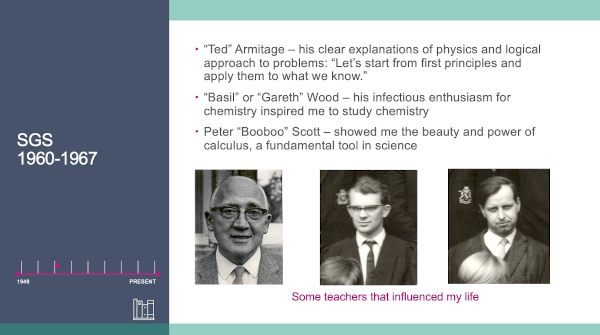

To finish here are the three teachers at Soham who were really instrumental in my Sixth Form science education.

| Ted

Armitage of course [Headmaster: Physics: 1945-72]. He

had such a clear way of explaining physics, that it seemed

easy. Starting from what seemed to be difficult problems,

you seemed to be able to unravel them easily. I remember him

saying "Well, it looks tricky, but let's start from first

principles and apply them to what we know." Gareth/'Basil' Wood [Chemistry 1964-72]. He was the one that really got me interested in Chemistry. He was so infectiously enthusiastic for his subject. I told him at the Old Boys dinner in 2012, the 40 years Anniversary Dinner after the Grammar School closed, that he was really the inspiration for me to go and study Chemistry. I'd like to acknowledge his wife Judith who would have joined us today had she not had a prior engagement. |

|

| Last but not least, I have to thank my wife, Elaine, who has stood by me on this long journey across different countries, continents, kids changing schools and, and then for the last 11 years really supporting me and working together in our partnership. |  |

John Dimmock SG59: Michael, thank you very much. That's been fantastic. A lot of technology, it just shows you how far things have gone in our lifetimes. Things that were unimaginable when we were at school. It's been a great journey, and you've been part of it. Thank you. [Applause]

Frank Haslam SG'59': Alan Dench SG67 was sorry he had to go. For him your talk brought back great memories of his time working for a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary in New Brunswick, New Jersey in the 1980s "I can concur it's an exciting industry to work in."

Prof Geoff Fernie SG59 in Toronto says "Brilliant talk Michael", which I'm sure we all echo. [more messages like this have been received]

Dennis Wilkins SG53 asks "Michael, can you give us some insights into what you feel AstraZeneca did right and what they could have done better with the COVID vaccine?"

MY: It's interesting you should ask that because when I was working with Aventis, our head of Global Marketing at that time is now the CEO of AstraZeneca. It's a difficult question to answer, because we don't really know all the facts. But let's say it has been reported that there were some irregularities in their clinical trials.

There were some very confusing reports that came out early on. They weren't sure, I think, in some trials, what dose had actually been used, or they thought they might have used some vaccine vials that hadn't had the correct amount in, or something. It was all very confusing.

But unfortunately the outcome has been that the AstraZeneca vaccine is not yet approved in the United States. We have three approved vaccines, the Moderna, the Pfizer/BioNtech, and the Johnson & Johnson. AstraZeneca is not yet approved here. I don't even know the status of it to be honest.

I know in the UK, the AstraZeneca vaccine has been used widely, and I'm sure it is an excellent vaccine. And it's been widely used in in many parts of the world. But as far as the US Food & Drugs Administration is concerned, I think they have been very cautious about moving it forward. So that's about the best answer I can offer.

Who registered for the 2021 Reunion? And who sent apologies?

Report on our 2021 Reunion

To comment on these stories or to

add more to those shown, or to add new stories for our website, please contact the editor.

page last updated 25 Oct 21