Mike Barningham

The title of my

piece could equally have just as easily applied to my school report as

my meanderings across the globe.

Where to start? I can boast that amongst my ancestors of a century or more ago, were industrialists like my great great great uncle William Barningham, an iron and steel magnate, who was born in Arkengarthdale, North Yorkshire in 1825, one of eleven children. He was a self-made man. He ended up, in his Darlington and Pendleton foundries, producing railway lines for the fledgling railways of North America and the Empire. He was the first man to own and use a Bessemer converter in England, was one of the richest men in Britain and, reputedly, a thorough going, down-to-earth alcoholic with a vile temper. His obituary finished:

So money isn’t everything.

My father, my two uncles and my aunt, were all born in the same public house, The Red Lion, Langthwaite Arkengarthdale in North Yorkshire:

Alas none of his wealth ever trickled down to our side of the family. We did seem to have a talent for global travel way back then. Three of our lot went to America in the late 1840s, two into railways from the William Barningham foundries and one into lead mining. There is a Barningham Road in Richmond Virginia, where there was a steel rail stockyard. Nathanial Barningham, then living in Swaledale, was deported to Australia in 1843 - for sheep rustling.

My father escaped Arkengarthdale at seventeen, almost a century later in 1936. He joined the Royal Marines. On 10 May 1940 he had been on the raiding party which invaded Iceland, the same day that Guderian’s panzers were breaking through the French at Sedan. He sailed to Dakar on the Ark Royal and disembarked at Gibraltar two days before she was sunk. He trained on Landing Craft and was a Landing Craft Coxswain on D-Day. He went on the Reserve in 1947 and married my mother. She had just come back from Germany, having served in 21 Army Group and on the post-war Control Commission.

So where did my inclination for travel start? I was born in St Stephen’s Hospital Chelsea London, on 7th October 1948. When I was a year old my father was recalled to the Marines for the Malaya Emergency, but instead wound up in Korea in 41 Commando. My mother and I lived in a third floor flat at No 1 Great Cumberland Place, overlooking the Marble Arch. My mother was the deputy manageress of the Euston Tavern (now called O’Neill's) opposite King’s Cross Station.

No 1 Great Cumberland Place

I am told that at two years old, in the summer of 1951, my cot was up against the open window. I had crawled out onto the window ledge, fifty feet up. The Fire Brigade arrived with the Police, before my poor mother had discovered my penchant for travel at altitude. I think she was on sedatives for a week. Were it not for an alert passer-by and the London Fire Brigade, my travelling inclination, would have ended right there.

The Bermuda Triangle is the mysterious phenomenon, famous through the ages, for all manner of men and materials vanishing into oblivion. The Barningham Triangle, is much more simple. They all seem to have vanished into pubs after service in the Marines, Army, or the police.

Thus when my father returned from Korea in 1952, he and my mother, following the pull of the family gene defect, vanished into the pub trade, first as manager of The Falcon in Clapham, and then as tenant in The Geldart in Cambridge, a Tollymache pub opposite the Co-op dairy.

At the age of six, I attended the Shrubbery School on Hills Road, cycling across town through the traffic in all weathers. Quite normal in my day, but I wonder what British 'elf 'n shafety' would make of that, with mummy’s little dears of today wrapped up and strapped in to mummy’s recreation vehicle.

From crawling on to elevated ledges at two, I graduated at the age of seven to scaling the scaffolding on Cambridge building sites. Ever onwards and upwards. At the Shrubbery, boys' penknives were inspected by the sports master, to make sure we kept them clean and sharp for peeling oranges and trimming bits of wood. I also presumed that he didn’t want me to stab anybody with a dirty blunt knife. Where I grew up, in the back streets of Cambridge, a penknife and a bike were essentials for a boy. Owning a watch, even one with Micky Mouse and Big Ears on it, usually meant your parents were comfortably well off.

It was at that age that I began to take notice of all the aeroplanes in the sky, around Cambridge. The father of a school friend was based at Bassingbourn, an RAF navigator on a Canberra B6s. I often stopped over at his place in the Officer’s Married Quarters at weekends while at junior school, spending my time on the end of the runway with a pair of binoculars that my mother had looted from Germany. Probably time better spent than climbing 70 feet up the scaffolding of the new Co-op bakery chimney.

I passed my 11+ and for my sins wound up here at Soham, where the next five years would prove that, at the time, I had little academic inclination. Travelling daily from Cambridge I developed a pathological hatred of buses. My mother was a devout Christian, my father not so much. I was packed off to Sunday School at St Barnabas Church on Mill Road. I really, really, hated it. I was, by the age of eleven, quite capable of my own interpretation of the scriptures. I decided on one sunny day to go for a bike ride instead. Armed with the binoculars,and an OS 1 inch map, I cycled to RAF Waterbeach to observe the Hawker Hunters based there.

It was six weeks before I was rumbled. My mother had assumed that after Sunday School I had gone round to a friend's place in Mawson Road. His mother said she hadn’t seen me. I had managed to visit RAF Waterbeach once, RAF Oakington once, RAF Duxford once and Marshall’s Airport three times. I handed back the money my mother had given to me for the collection and nothing else was said. I had learned how to read a map.

I joined the Air Training Corps at thirteen and a half and developed into an air force mad Air Cadet. I attended my first summer camp in the summer of 1963 at RAF Marham, then a V-Bomber base operating Valiants.

104 (Cambridge) ATC Squadron Summer Camp, RAF Marham, August 1963.

Mike Barningham 2nd row up, extreme left.

104 City of Cambridge Squadron was a very fortunate squadron. We had the full support of Sir Archibald Marshall. No.5 Air Experience Flight and the University Air Squadron were based at Marshall’s, a couple of hundred yards from the Squadron HQ on Newmarket Road. With Training Command at RAF Oakington, operating Varsity transport trainers, and ten or eleven other operating RAF stations within a thirty mile radius of Cambridge, opportunities for visits came thick and fast.

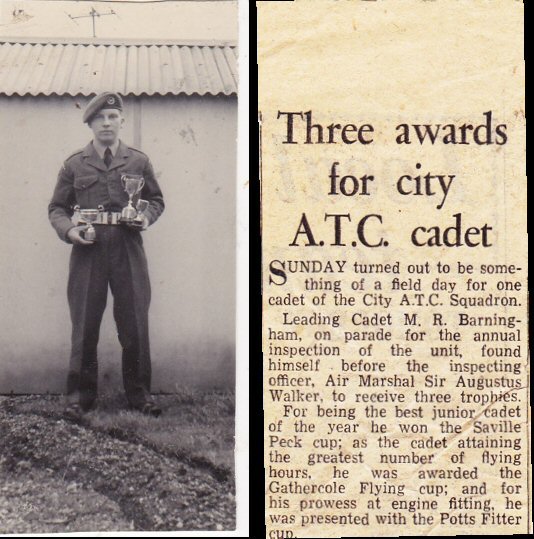

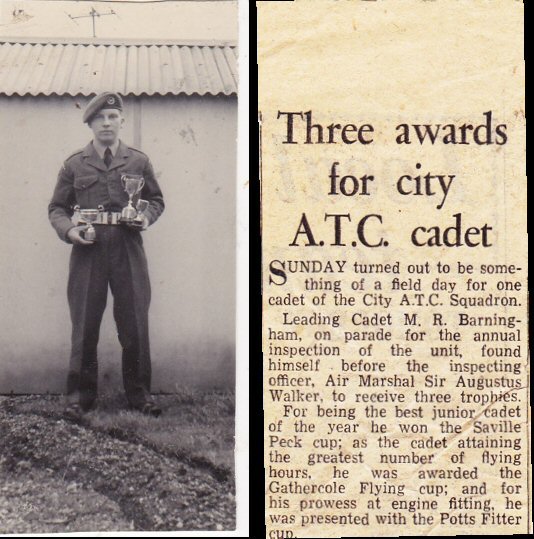

More and yet more ATC and the summer of 1964 saw me on Annual Inspection, with a mention in the Cambridge News.

There were four Soham Grammarians at our 1964 Summer Camp at RAF Finningley, another V Bomber base operating the Vulcans of 617 Squadron:

The four Soham Grammarians: Mike Barningham (back row, extreme left); Charles Holleyman (back row, 4th from left);

Mark Taylor (back row, 5th from right); John Shelley (back row, 2nd from right)

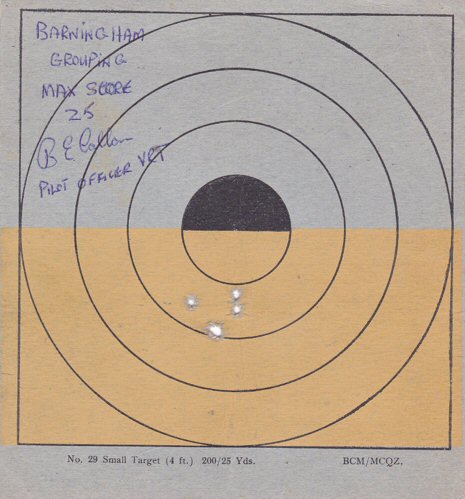

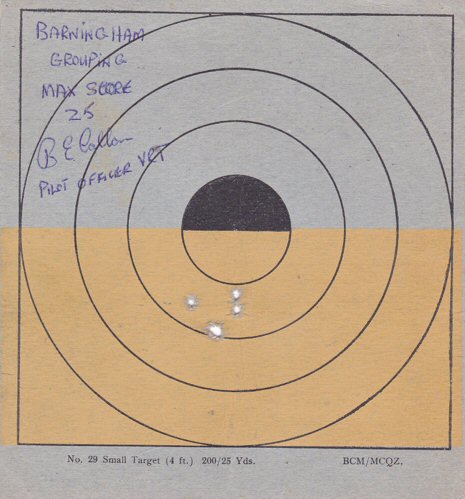

As Captain Speed and Captain Scott will possibly recall I paraded with the SGS Army Cadet Force, in Air Cadet uniform, with Mark Taylor, John Shelley, Lawrence Arthur and Charles Holleyman, who I had recruited to the ATC. Brian Callan, the Science Lab technician who held an RAFVR(T) Commission in the Downham Market ATC Squadron, also mucked up the khaki ranks by parading in air force blue. He ran the rifle range.

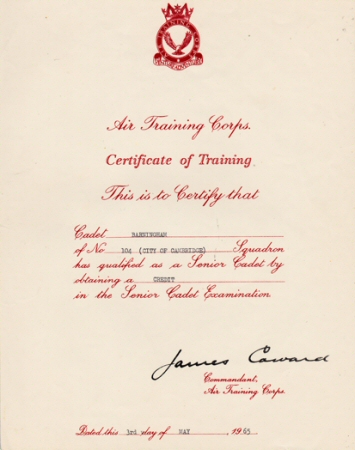

I reached the rank of Cadet Sergeant at sixteen, resplendent with Senior Cadet and Marksman badges, complete with solo Glider Pilot Wings gained on course at RAF Halton. I had amassed a total of 62 flying hours on Chipmunk T Mk 10s of No.5 Air Experience Flight and the University Air Squadron, both at Marshalls Cambridge - and in the Navigator seat of Varsity transport trainers based at RAF Oakington. I attended camps at RAF Marham, Finningley and Ternhill. I also did the ATC Outward Bound course at Keswick

My week was very busy. At six thirty each morning except Saturdays, I cleared the empties, filled the shelves, wiped the tables and cleaned the ash trays in my dad’s pub for four shillings pocket money each week.

On Wednesday evenings I paraded at the Squadron HQ.

On Thursday evenings, I cycled nine miles to RAF Oakington to hang around for an opportunity to fly with RAF Training Command.

On Fridays I paraded in ATC uniform with the SGS Army Cadets.

On Saturdays, I was up at four and on a milk float, heading for Histon, Cottenham and Rampton with a Co-op milkman who wanted to finish early on Saturdays. He took me on to help deliver milk for half a crown for the morning. I was leaping in and out of the moving open door milk truck, grabbing full milk bottles, running to the door step and returning at the run with the empties. Modern Health & Safety would probably go into cardiac arrest. By noon, I was hanging around 5 AEF hut at Marshalls in ATC uniform, or the University Air Squadron line office.

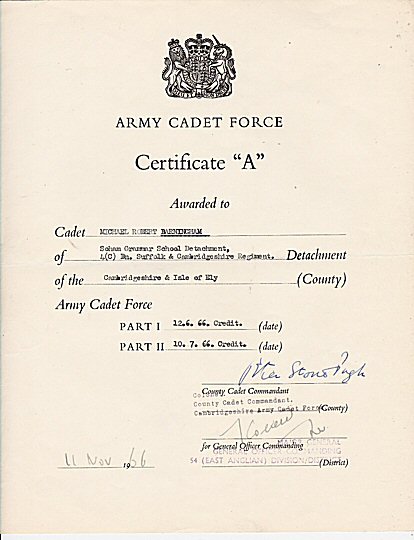

Sunday morning I paraded at Squadron HQ and Sunday afternoon I was back at Marshalls, hanging around for an opportunity to fly. Bill Ison, of the Tiger Group at Marshalls, who owned the cycle shop in Chesterton, was a customer in the pub, and I flew in a Tiger Moth on three occasions. I also passed ACF Certificate A Part I and II, with the SGS ACF.

I did manage to give grammar school my full attention on Mondays and Tuesdays, but only if nothing more important was happening. I paid heavily for the lost attention to school work later. I think that of my academic achievements at Soham, it could easily have been written of me "Sets himself ever lower standards, which he consistently fails to achieve."

Form 5T/Alpha Summer 1965 - more photos

5T photo top L-R: Mark Taylor - Colin Blackwell - Philip Rowe - Andrew Crane - John Seaton - Lawrence Arthur

upper middle: David Camps - Richard Butler - William Wheeler - Roger Creek (partially obscured) - John Bailey

lower middle: Geoff Griggs - Michael Barningham

front : Michael Murfitt - Ian Middleton - Tom Gray

image: taken by Alan Bray

A few months after my ‘O’ Levels, we moved to The King’s Arms Hotel

in Ivybridge, Devon. It is now renamed The Exchange and owned by

a plastic pub chain, wiping out three hundred years of history in their

race to the bottom.

formerly The Kings Arms, Ivybridge, Devon

At the time, not being remotely interested in staying at school and having neither inclination nor natural talent for anything of use in civilian life, I started applications for the armed forces.

To my disappointment, the Air Force didn’t want me in any capacity that I wanted them. I didn’t at the time see myself in the Navy.

I passed the War Office Board for the Army and was offered a limited service commission, but that would have meant going back to school at the Army School of Education at Beaconsfield to complete ‘A’ Levels and a commission through Mons Officer Cadet School. At that time I didn’t want any more school.

I passed the Admiralty Interview Board for a Commission in the Royal Marines, which only required five GCE ‘O’ Levels, presumably because nobody bright enough to pass A levels or sane enough to realise the many opportunities for serious injury, or worse, would consider the Marines as a career. However I did not pass high enough on the list of qualifying candidates for a place on the next Young Officer Entry. So I enlisted. Green Beret first, Commission later, with my eye on aviation.

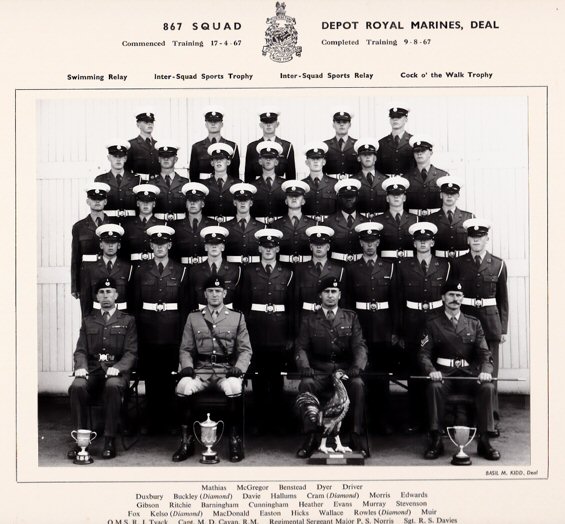

Thus I joined 867 Squad of the Royal Marines - proving I wasn’t Air Force Mad, just mad. My life insurance premiums went up - my mother was back on sedatives. I told her to look on the bright side - after rejection by the RAF, I had seriously considered the Foreign Legion and the US Army.

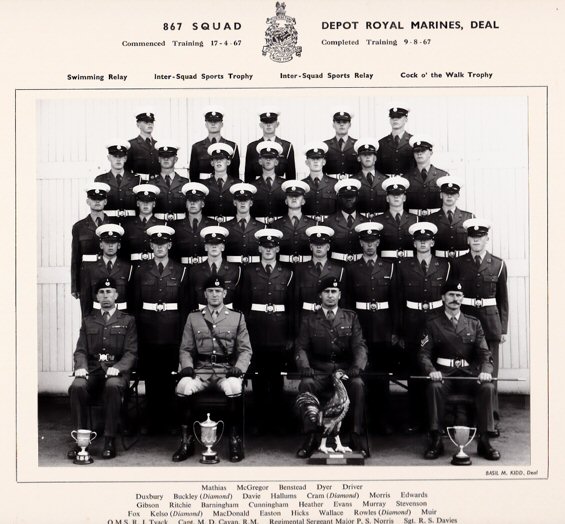

Down to Deal in Kent, where I signed on and got the Queen’s Shilling, along with DMS boots, puttees, denims, a scrub belt and a Navy Beret, with an RM Cap Badge, plus a set of tin mess tins. I was ‘Introduced’ to one Sergeant R Davis RM. It wasn’t the bolt through the neck or the zip up the back of the head (that the collar, tie and green beret did little to conceal) that told me that I might have a problem if I upset him - and he probably got upset very easily. It was those piercing, laser eyes. His gaze was like something out of a very grisly Neanderthal science fiction movie. They could see right through you - and the man standing behind you. They also worked simultaneously out of the back of his head. The squad loosely assembled for the first group photo.

Royal Marines 867 Squad, April 1967: Mike Barningham front row, 3rd from left

Thirty three started. How many would finish with the 867, if at all? The smiles were very quickly wiped off our faces. The object of the first ten weeks training at Deal was to get you physically fit and mentally conditioned for what was to come, or back-squadded - or out. The process involved killing any lingering civilian characteristics and extinguishing any thoughts of a glamorous image. Life was harsh. PT in the Gymnasium every day except Sunday. Pull-ups, sit-ups, rope ascent to the roof, and running as a squad - drill followed by more drill. Weapons training, the range, kit musters, bivouacking, yomping up to Cold Blow field. Break camp, make camp. The pace increased as the weeks passed.

Six weeks in, I got into sailing at Deal and crewed one of the Corps' yachts, the Sarie Marais, from Dover to Boulogne over a long weekend. I had phoned my parents and let them know I was sailing to France. As things turned out I probably should not have done that. With the Royal Naval Education Branch Lieutenant Commander as skipper, seven of us had sailed out of Dover Harbour for a night crossing on the Thursday evening, tied up alongside amongst the Boulogne fishing fleet and proceeded ashore to immerse ourselves in French culture.

The Colonel of the Depot, H. Maude, had sailed over in his own yacht with his wife, a day behind us. He tied up alongside the Corps yacht and came aboard, to find us all seriously four sheets to the wind after a liquid French cultural experience still very much in progress. “I think it is time that you started back for Dover.”

It was not a hint, or a birthday greeting, it was an order. We slipped and followed the Colonel and his lady out of the harbour. The sea was cutting up rough and it was night, the radio had failed. The skipper wore quite thick glasses. He decided to do the sensible thing. Without radar or radio, in bad weather, with an inexperienced crew and with oil tankers plying the Channel at ninety degrees to our course, we went about, put back into Boulogne, tied up alongside and went back on to the French culture to wait for a break in the weather.

The Colonel carried on, oblivious of our change of course, arrived in Dover. He waited ... and waited ... and waited. No Sarie Marais. He couldn’t raise her on the radio. He reported to the Harbour Master, who sent out a shipping alert. It made the national press, ‘Marines lost at sea.’ My mother saw it and was back on tranquillisers. The Boulogne Triangle was not unlike the Barningham Triangle - we weren’t lost, we had just vanished into a French pub. When we got back the following day the Colonel was not at all amused. The Lt Commander took all the flak.

The remainder of my time at Deal passed without incident. We had managed to complete our seamanship training at HMS Bellerophon, Whale Island in Portsmouth, living aboard a World War II Corvette, the Volage, with mess facilities on board HMS Belfast (these days moored in the Thames). We were becoming bilingual, picking up 'jack speak' - where toilets were the heads, the padre was the sky pilot and RM officers were pigs.

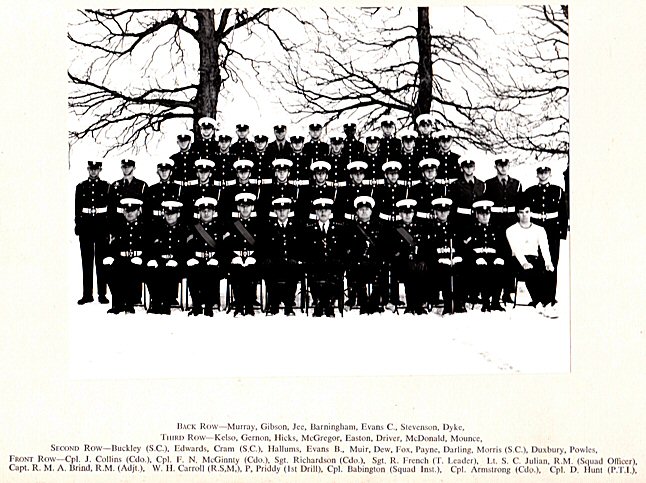

After seventeen gruelling weeks 867 Squad marched through Deal to the station, to proceed to Infantry Training Centre Royal Marines Lympstone. My sixth home. We had lost some on the way and picked up some back-squadded individuals, including two who the judge had given the option of five years in jail or nine years in the Corps. They were fast coming round to regretting their decision.

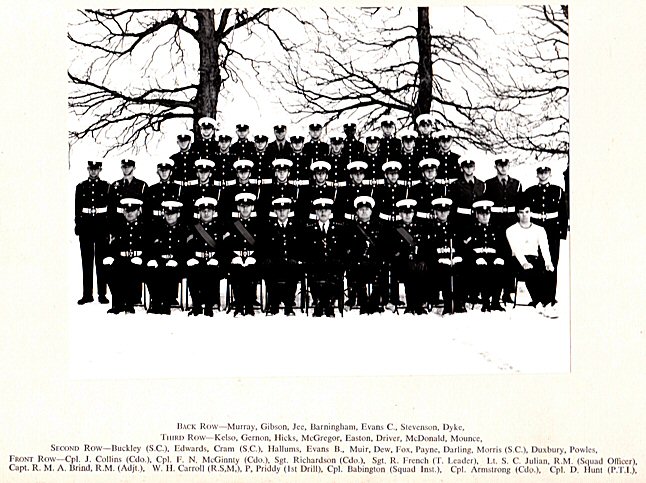

867 Squad Royal Marines August 1967 - 28 of the originals left

We disembarked at Lympstone station and were met by one Sergeant MacMillan, otherwise known as the Poisoned Dwarf. Sergeant Davis was a pussycat compared to MacMillan.

The object of B group training, more accurately described as violent physical abuse, was to see if they could make any of us crack. The secret here was a warped sense of humour. You would always mock the afflicted, sympathy was for civilians. They were relentless and life became tougher and tougher. We spent a lot of time on Woodbury Common, though why they called it a Common I will never know. Although there were no fences, civilians never went near the place. It was a plantation of thorn bushes, specially designed, cultivated and arranged to guarantee penetration of combat gear no matter in which direction you crawled.

You slept whenever you could, you did not know when the chance would come again. It rained nearly incessantly that year, to magnify the discomfort. We were perpetually saturated. If there was a dry day, they would find a manky stream for us to crawl through. When we weren’t in the field there was the assault course, the gym, followed by more night exercises on Exmoor and Woodbury Common, and more weapons training. A few more 867s dropped out and we picked up a couple more back-squadders.

We went to RM Hamworthy in Dorset for Small Boat and Landing Craft training and to Jennycliff in Plymouth for Cliff Assault Training.

A marine in training would burn 3,500 plus calories per day. Food is nothing but fuel. You never threw food away, you had to carry it and throwing it away would mean you had carried it for nothing. The training seemed to go on without end, but it did end after thirty four weeks with the four Commando tests and Passing Out parade.On the first three tests you carried twenty four pounds of equipment and a rifle. All tests were completed the same week:

867 Squad Royal Marines December 1967 - 21 of the originals left

I was a Candidate in Waiting for a commission from the day I got my green hat. But first, I was to sample the delights of a tropical paradise, when my name went up on orders for a draft to 40 Commando in the Far East. I was thinking Chinese Birds and WRAFs, Wrens and WRACs, but not necessarily in that order. Was I in for a shock.

I gleefully ascended the boarding steps of the British Eagle Britannia, a four engine turbo-prop, departing Heathrow. We refuelled at Istanbul and Bombay (Mumbai), landing at Paya Lebar in Singapore. I had reached journey’s end and arrived in the land of the midnight fun. Or so I thought. Still jet lagged, I was rushed to Sembawang airfield, half asleep and clattering around in the back of a three ton truck. I was greeted by an irritated storeman with: "We are rear party and you are not. The unit is up country. You leave tomorrow, at 0700. You are joining C Company."

Issued with a Self Loading Rifle, Machete and the usual Olive Green fashion array which was topped off with a floppy hat, I stood resplendent in the British stores speciality of canvas and crepe self-dissolving jungle boots. Unlike Nancy Sinatra, we found out the hard way that these boots weren’t made for walking. In fairness the canvas never rotted, there wasn’t time for it to rot. The glue dissolved in warm water. Not surprisingly in the jungle (or Ulu) there was rather a lot of it.

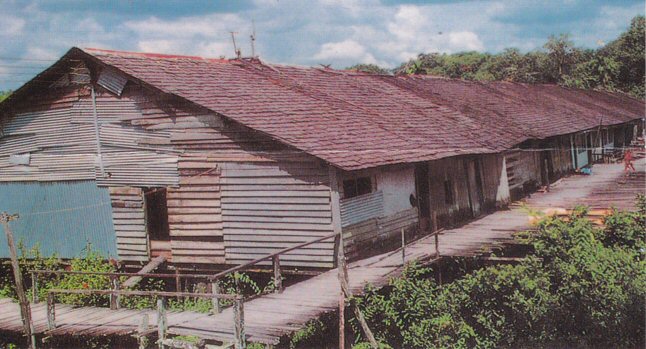

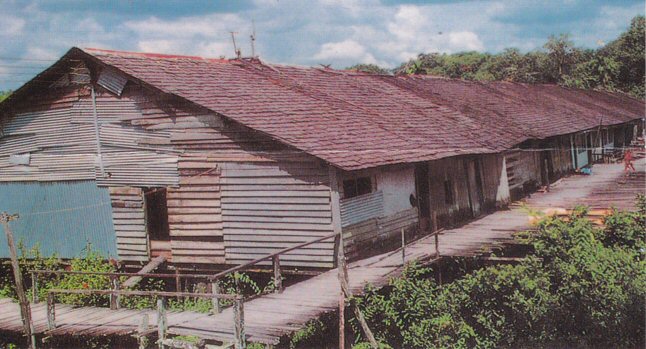

Not the Kuching Hilton

The sheer luxury of the Kuching Hilton was not for me. I joined 5 Section, 8 Troop, C Company 40 Commando Royal Marines. Amongst the flora and fauna I was welcomed by my section corporal. Make yourself at home is what I thought he said. What he really said was make yourself a home. I was paired off with the lead scout, who carried a much coveted 5.56 mm AR15 Armalite rifle which was fully automatic, rather than the 7.62 mm SLR which was not and weighed twice as much. Weight in the jungle was your enemy, we even cut most of the handle off our tooth brushes to reduce weight.

I made the fatal error of asking how I could get an Armalite. The troop sergeant overheard and asked if I really wanted to swop my SLR for another weapon. “Ooh yes please.” Straight in it. They took my SLR and handed me the Section’s General Purpose Machine Gun, three times the weight of an SLR. The only consolation was that I was guaranteed to hit something if I ever had the misfortune to use it. As I was a Candidate in Waiting for a Commission Sergeant Frank Gilhooley took perverse pleasure in giving me the full benefit of his repertoire of undiluted hatred of officers, actual and potential.

Home is where you make it

This was home on and off for five weeks when I was not out on armed nature walks strolling through the Ulu, dissolving British jungle boots.

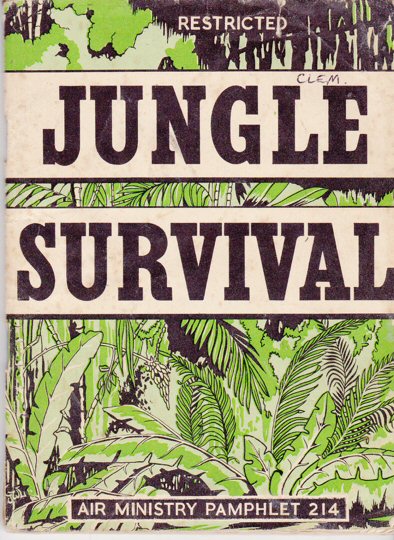

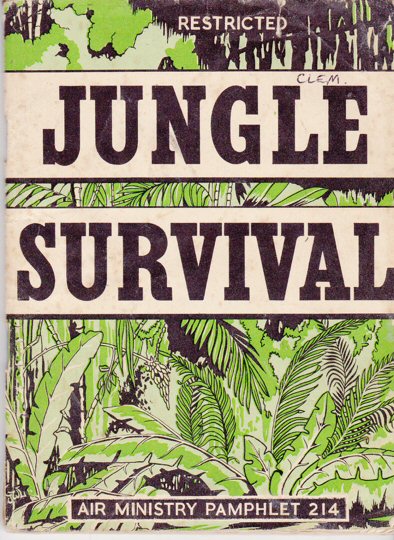

I had been issued with Air Ministry Pamphlet 214, written by an expert, to alert me to the dangers of the jungle. One paragraph was devoted to what you did if confronted by an elephant advancing on you - “Run downhill.” So there I am waist-deep in water in the middle of a rice paddy, thirty pounds of GPMG plus ammo slung round my neck, this big grey thing is getting bigger and I am supposed to look for a hill to run down. The Navy had gained a new item in jack speak when Chad Valley came out with games for children which didn’t do what it said on the box. Something that didn’t work became Chad.

The grief felt after the loss of a pet can be every bit as painful as that following the death of a human, so why didn’t we take it so seriously in the Marines?

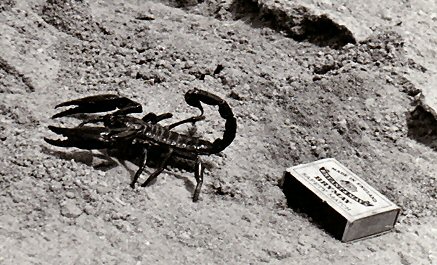

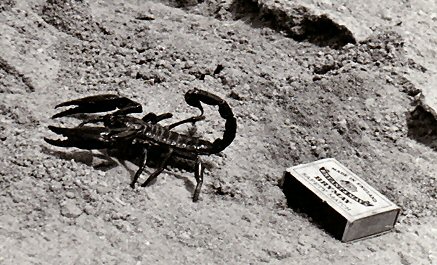

It really depends on the pet. Here is one reason:

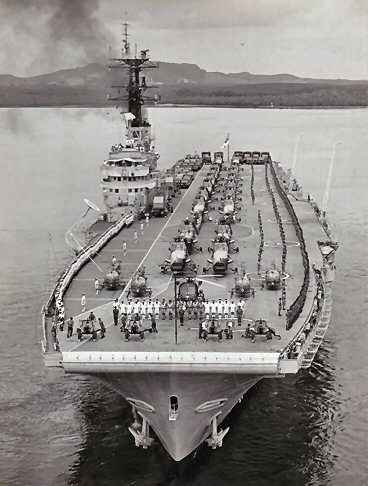

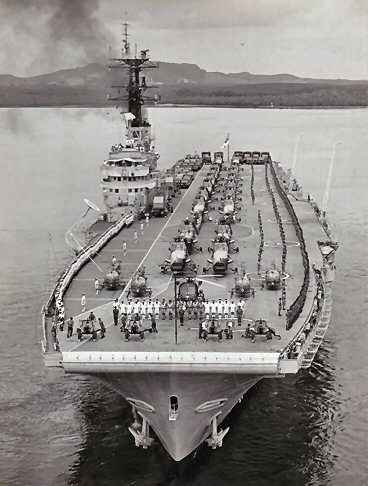

I did managed to ‘procure’ a pair of stitched Australian jungle boots which were fit for purpose, just in time to no longer require them as we embarked on the Commando Carrier Albion to sail off to the Gulf of Aden where DMS boots would be the order of the day. Harold Wilson had decided to cut the cost of us being in Aden from £60 million a year to £12 million. I completely failed to see why we were paying anything at all as they had moved into the Russian sphere of influence, but there were still Europeans left in Aden and we were being sent to stand by to get them out if things got nasty.

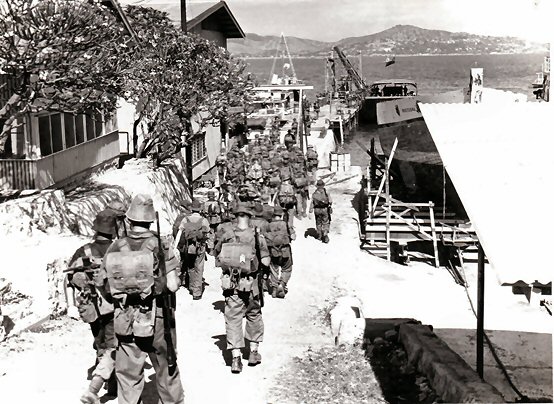

40 Commando embarked on HMS Albion for the Gulf of Aden, March 1968

Fortunately peace and tranquillity prevailed and we sailed to Mombasa, a place with every disease known to man and quite a lot that were not, then to RAF Gan and back to the Far East and Singapore.

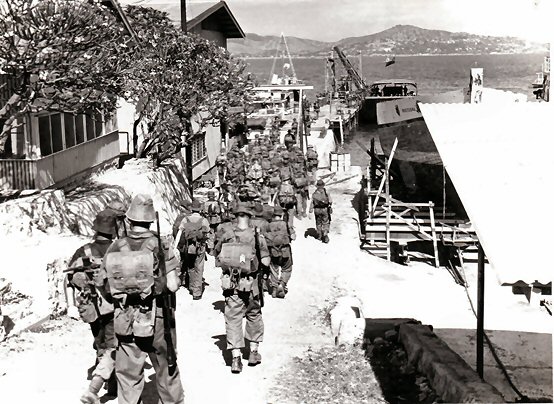

Continual exercises in the Malayan jungle became the norm, until we sailed on the Landing Ship Logistic Sir Geraint to Australia, via the Timor Sea and New Guinea, where we did a nine mile speed march at 95 in the shade. The locals thought we were crazy. Three cases of heat stroke proved that they were right.

C Coy 40 Commando 9 mile speed march Port Moresby, New Guinea. October 1968

On to Australia, for exercise CORAL SANDS, a huge SEATO affair, involving the armed forces of four countries. 40 Commando were landed at Shoalwater Bay near Rockhampton. We had been warned that Australia had more crawling nasties than everywhere else on the planet put together. We were warned to watch out for the snakes particularly the Coastal Taipan - which if you were bitten by one, without the antidote it would prove fatal. The problem was that there were one hundred and four known variants.

Friendly Queensland local. Coastal Taipan come to say hullo.

We were told that if bitten you must kill the snake and bring it back, so they could administer the correct serum! We were also told that we had about two hours to get medical attention. I saw two Taipans and a King Brown, which was OK. It was the ones that you didn’t see that would be the problem.

We chased enemies simulated by 800 Gurkhas all over the bush. Over the following week I think we caught one. Then on to the important part of the exercise. Shore leave in Brisbane.

The Aussies threw the town open to us and by and large, we behaved ourselves. The girls, the pubs and the climate were great. Several marriages were to occur as a direct result of our run ashore in Brisbane. How different from Britain, where the sign ‘NO SOLDIERS OR DOGS,’ was sported unchallenged in some pubs. I was getting the first glimmer of where I probably wanted to go when I left the Corps. When we sailed for Singapore, a dozen marines were AWOL. Most were arrested and returned, but I think a couple of them are still missing. Many British ex-service personnel were to find a home in Australia.

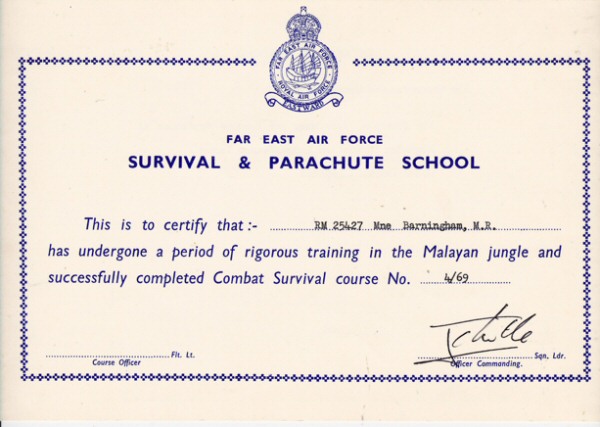

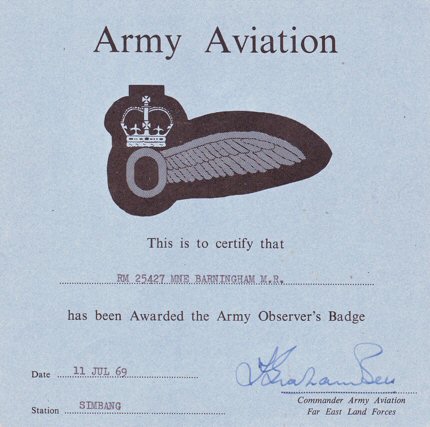

After CORAL SANDS I applied for and got transfer to the Air Troop and trained as an Army Air Corps Observer, picking up para wings on the way.

The Air Troops of 40 and 42 Commando, HQ 3 Commando Brigade and 95 Commando Light Regiment Royal Artillery were combined to form the Third Commando Brigade Air Squadron. I spent a year with them and learned a great deal. It certainly beat yomping through the Ulu, dissolving British jungle boots. I could see the reasoning behind the late, great, Peter Ustinov's comment when he was called up for war service. He was asked why he wanted to join the Tank Corps - he said if he had to go into battle, he wanted to do it sitting down.

In July 1969 I was seconded with an Army Air Corps unit to S(h)ek Kong Airstrip in the New Territories. When I arrived back in Singapore my tour was over and I was posted back to the UK.

When I got back to England in September 1969, I had been recommended for a Commission. I opted for aviation and passed Aircrew aptitude tests at the Officer and Aircrew Selection Centre at RAF Biggin Hill. In early 1970 I attended an officers' knife and fork course. It was for uncouth other ranks like me, possessing all the grace and charm of the Army of Anubis. We learned from Group Captain Stradling’s book, Mess Etiquette, that it was the bread knife that went on the extreme right, not the bottle opener.

My mother passed away with cancer, in April 1970, while I was on the Officers' Course.

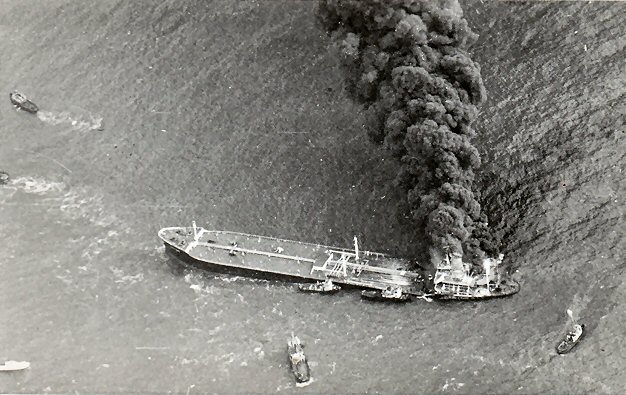

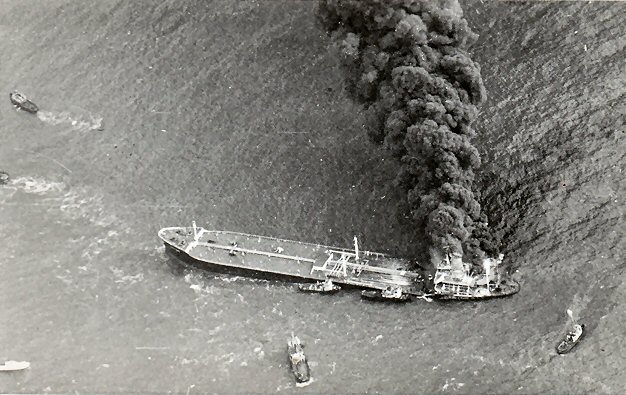

Pacific Glory touched bottom off the Isle of Wight after collision with the Allegro, 23rd October 1970

An incident at sea. In the early morning of 23rd October 1970 I was in Portsmouth and saw a fire at sea and a huge smoke plume. I headed for the Portsmouth Flying Club with a borrowed camera. I got there just in time to join the CFI and a reporter from the Telegraph. It was the Pacific Glory burning off the Isle of Wight following an explosion after collision with the Allegro, another tanker. Thirteen of the crew died in the explosion.

I had looked forward to a military flying career. I had picked up my civilian flying licence on the way. Alas it was not to be. Impending withdrawal East of Suez saw immediate cut-backs and in early 1971 I found myself permanently back on the ground. There was talk that the Royal Marines would be disbanded, doing wonders for morale and recruitment. The RAF still didn’t want me. They too were heavily cutting back. The Royal Marines meantime were reinventing themselves, with a snow warfare role. I did not relish continuing with the prospect of the relentless Belfast triangle of Northern Ireland, Norway, Scotland. Rotating through 41, 42, 45 and 40 Commandos I saw promotion prospects as severely limited. At best I would only ever finish up as a special duties Lieutenant in a recruiting office after years of shuffling logistics.

It was time to assess my situation. If I was not going for a full career in the Marines, it was better to leave sooner rather than later. I had started to think what for me a year earlier would have been unthinkable, leaving the service. For civilian career prospects, I realised I would be playing catch-up with my civilian counterparts. I had started intense study on an A Level course in Pure & Applied Maths, through the RN Education Officer and correspondence with Highbury Technical College Portsmouth. I passed my A Level in 1972 and decided to leave at the end of that year. In my case it was the right thing to do. I had again been told that there were no prospects of getting back into flying. I was not going to be happy doing anything else in the service.

After six years, I had walked away with an A Level and a civilian flying licence. I was still in one piece and very fit. Do I regret my time in the service? No. I had done time in one of the toughest outfits on the planet and had seen a lot more of the world than I ever would have done in that period of time as a civilian. The decisions of politicians to scrap the Fleet Carriers heavily impacted British military capabilities.

What next? My options:

Join the US Army? Out of the frying pan into the fire.

Join the Foreign Legion? Ditto and five years for a French passport.

Join the Hong Kong Police Force? Incubating the gene defect of the other half of the family. They were recruiting heavily in the UK, following a corruption scandal. But I realised that there must be more to life than strutting around in Eric Morecambe shorts and climbing in and out of Land Rovers looking Trevor Howardish.

Australian Air Traffic Control? I had passed the interview board and aptitude tests at Canberra House and was set to emigrate, when Harold Wilson decided to have a difference of opinion with his Australian counterpart over visas for Australians. The Australians stopped all civil service recruiting from Britain just before I was due to go. Politicians again.

The Ordnance Survey? I had an avid interest in maps and applied for Land Surveyor. In the meantime I joined Ciba-Geigy at Duxford to earn money to feed my flying habit, manufacturing bonded structural aircraft component parts. While at Ciba I bumped into John Beer, Robert Reynolds and John Holland, all Soham Grammarians who had travelled with me on the Cambridge bus.

I was accepted by the OS to train as a Land Surveyor and left Ciba for Southampton in May 1973. I stayed in the YMCA throughout my course, but I ate in the pub. I did well on the Surveyor’s course and was posted to Camelford in Cornwall in May 1974. There were three of us mapping from air photographs and ground survey, across North Cornwall, at 1:2500 scale. I lived in digs between Boscastle and Tintagel, 300 yards from the cliffs and overlooking the sea. I walked over every inch of a third of North Cornwall. When we completed the North Cornwall section, we moved the office to Holsworthy in North Devon in December 1974 and I rented a semi-detached cottage at Halwill Junction, a sleepy disused railway halt closed under the Beeching axe. They have since built a huge housing estate where Stagg’s Wood used to be.

From Devon, I was posted in April 1975 to Cardington Aerodrome near Bedford. I met the late Bob Monkhouse while I was surveying his property in Eggington. In December 1975 I was again posted, this time to Hertford. I met Sue Ryder - our office was above her charity shop in the Arcade. Then to Harlow and on to Bishop’s Stortford ,where I met Sir Henry Moore when surveying his property in Perry Green.

I enrolled in a part-time evening course at the Cambridge College of Arts & Technology, going for a second A Level in Geology. I was transferred up to Brooklands Avenue in Cambridge. I was unmarried, but bought a house at Bar Hill, which we still own. I passed my A Level. Now with A Level Maths and Geology, I was seriously considering reading for a degree in Land Surveying, but had a £4,000 mortgage to consider first.

Bar Hill, 1976

In February 1977 I saw an advert in the Daily Telegraph for a Land Surveyor in Saudi Arabia and picked up the phone. The OS as a job was fantastic, with flexi-time I was virtually my own boss, I worked mostly outside, moved around, stayed very fit and met very interesting people in the course of my work. It was a job for life, with a pension - if I wanted it. The drawback was lousy pay, at £2,200 per annum - and at the top of the pay scale, no prospects of advancement for decades. Dead Men’s shoes. If I had won the football pools I would have stayed and done the job as a hobby.

The Arabian Engineering Bureau were offering six times that, tax free, all found, vehicle, six months on two weeks off. They were having trouble keeping people for more than a couple of months, because the conditions were harsh and you needed to be self-reliant in remote places. Family separation of six months meant that married men would avoid this contract. They preferred ex-service single personnel for those reasons.

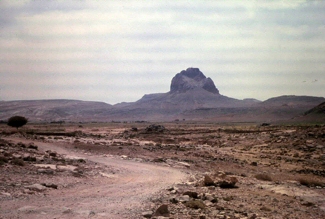

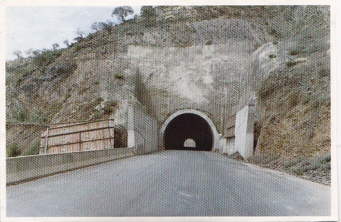

With sadness, I resigned from the Ordnance Survey and left for the Empty Quarter in Rojal Province, Saudi Arabia, where I swapped my sketching case, tape measure and Wellington Boots, for a second reading theodolite and desert boots. My task was astro fix from the North Star for Latitude and the Greenwich time signal and highest sun shot local time to calculate longitude. I was to set out main monument markers for a road and tunnel project, then set out the road centrelines and transition curves from those monuments. I slept in the truck and drove up to 40 miles across the desert to buy water and food.

After six months I was told that I would be transferred to a housing project on the West side of Dharan, in Eastern Province. I was to learn a great deal about the mindset in this culture. It was a requirement of the building permit that, before any construction took place, the orientation of Mecca was to be established by a local cleric to ensure that no toilets were positioned so that the rear orifice was presented to the birthplace of Mohammed the Prophet and Islam.

I had calculated precisely the direction, on a Universal Transverse Mercator projection. I knew exactly to degrees, minutes and seconds, where the Grand Mosque of Mecca lay. Our wise old construction manager, who had years of dealings in Saudi, told me to keep the information to myself and to let the cleric ordain the direction, rather than have the company contradict him. He arrived and pronounced the direction. He was thirty degrees out.

The architecture of the buildings we were constructing was designed to avoid windows facing south wherever possible, for the purpose of keeping a minimum of direct solar radiation at midday from penetrating the structure. The toilets ended up facing Mecca, missing the Grand Mosque by a matter of feet. We of course said nothing.

My lucky break into the petrochemical oil and gas industries came while I was still in Saudi. In December 1977 a colleague told me he was going to work in Libya. They were looking for setting-out engineers on a petrochemical contract. I gave him my CV to drop in to his new company and he flew out. My father received a letter from Stone & Webster a week later asking when I could come for interview.

I had been in Saudi for eleven months and was overdue for leave. I flew back to the UK two weeks later, was interviewed and offered a contract on £14,000 per annum, tax free, all found, with eighteen days leave every twelve weeks. I paid off the mortgage on the house and returned to Saudi, to resign from the Arabian Engineering Bureau. I thanked them for the opportunities that they had given me, but stated that I wanted to get away from roads and housing into petrochemicals, oil and gas.

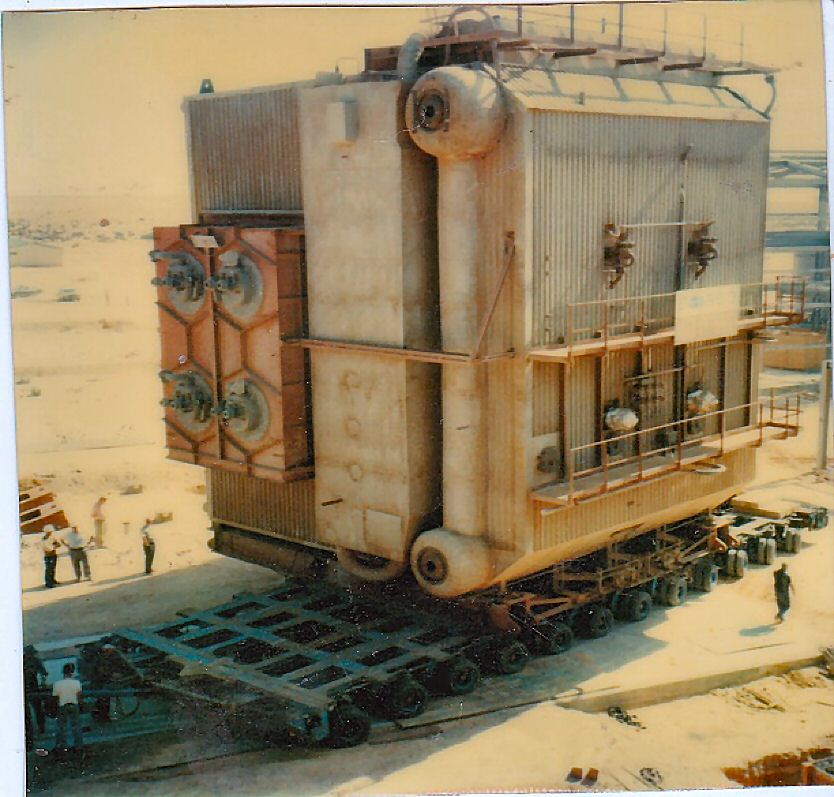

Stone & Webster Engineering. Ras Lanuf Ethylene Plant,

Libya

From March 1978 I spent eighteen months at Ras Lanuf setting out large foundation systems and aligning structural steelwork. S&W were feeding me away from pure surveying and were giving me tasks that suggested that I should consider going back to college to read an engineering degree. When they released me on completion of contract I decided that that was what I would do. Surveying was moving into electronics and automation, requiring few skills. It proved to be a good move.

It was while I was in Stone & Webster that I joined Expats International, formed by a former employee of S&W, Keith Edmonds. It was one of the smartest things I ever did, it kept me in employment for the next twenty-five years.

I returned temporarily to UK, bought another house for cash and rented it out. Via Expats International, in October 1981 my CV came to the notice of Technip, the French company, who were recruiting for a refinery expansion in Qatar. They offered me US$ 24,000 per annum, all found, a vehicle, three months on two weeks off. The French put all other foreign companies to shame when they work abroad. Technip Village at Umm Said, now spelt Memsaid, had a swimming pool, two yachts, tennis and squash courts, and a canteen that had waiter-served four course dinners with wine at every meal. The French ambassador was a regular attender. Françoise Hardy the French folk singer and Blaster Bates visited for entertainment.

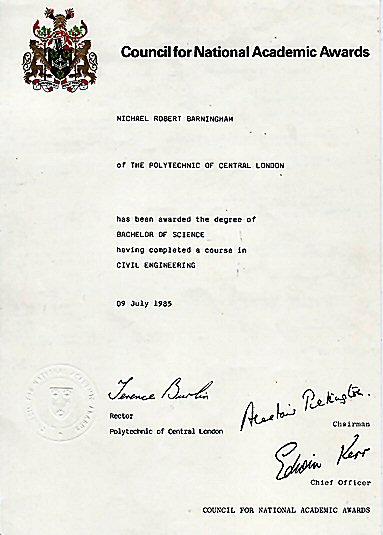

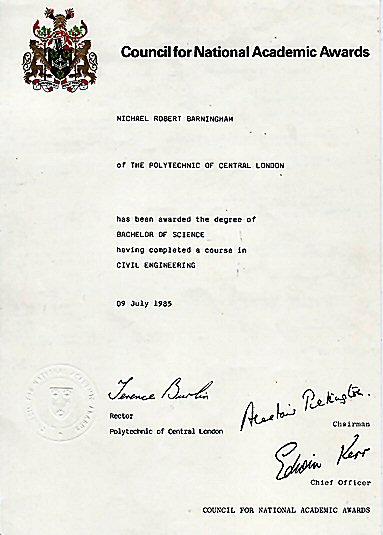

September 1982 saw me at the Polytechnic of Central London as a mature student, driving north to Huntingdon station to catch the 125 for King’s Cross. Ruth Madoc, the comedy soap actress, caught the same train most days - she was a scream. £3 per day return on a student rail card, carrying my Moulton lightweight folding bike and a fishing stool (there were never any seats on the train). Jim Tyne my college tutor, had designed the cradle that lifted the Mary Rose out of the Solent. The college had been selected by MoD (Air) on a contract to look into a potential vibration problem on the rear rotor of the Chinook helicopters that they were acquiring. I had opted for vibration of structures in my third year and was in on the act, which Jim Tyne was leading.

He said that the RAF was looking for suitable candidates for commission as engineer officers, and in conversation with them, my work had come up. They considered I had potential. They must have been desperate for engineers, asking me if I would be interested in joining the RAF twenty years after they had turned me down. It was far too late for me at thirty six, stuck on the ground and no danger of making twenty two years for a pension by age 55. I gave them a miss.

I graduated in July 1985, put out my CV to Expats International and was immediately offered employment by Brown & Root, returning to Ras Lanuf to sort out pre-commissioning problems, and for work on a pipeline at Zelten south of Marsa El Breqa. The offer was £36,000 pa, non-contributory pension scheme, vehicle, accommodation and food, ten weeks on eighteen days off, air tickets provided. I signed the contract on the spot and was putting my foot down occasionally to steer with, heading for the airport.

The work was a mixture of field and design office. I stayed with Brown & Root for three and a half years in Libya, a really good company. I was destined to work for them again later on the Libyan Great Man Made River Pipeline Project.

In 1986, the RAF wrote to me asking if I would reconsider. Nope, my service days were over. I needed a job that paid real money to feed my flying habit.

I put my CV out to Expats International and two weeks before I was released by Brown & Root, a really interesting contract came my way. It was with LG Mouchel & Partners, as a lead engineer on the design team of a coal fired power station at Yue Yang in China. We would be based in Hong Kong. It was a World Bank and British aid funded project. Don’t laugh.

My task was to design the turbine shed and turbine support plinths, with 50 metre spans thirty metres high. It was a fast track project and I commenced using British Codes supplemented with American Uniform Building Code specs for Earthquake Design.

After a few weeks of crunching numbers, we jumped straight into detail design, skipping all the usual preliminary work-up, and started sending drawings to GEC Trafford Park, the British supplier. I received a Telex from them asking me to hold. They would be sending me South African Design Codes, because, I was told, the steel would be procured from South Africa. The Codes were similar to DIN which produced heavier steel sections than the British Codes, not clever in earthquake zones where the whole idea is to reduce dead and live load at altitude wherever possible. It meant a much heavier design all round and more steel tonnage.

I later found out that GEC owned a steel plant in South Africa but in 1988 could not export profits generated in Rands without putting an equivalent amount in hard currency back into South Africa. So British Aid and World Bank money went to South Africa to procure steel for China, allowing GEC to export an equivalent amount in Rand. That is one way that aid money used to work - and probably still does.

In January 1989 the design work on Mouchell was winding down and I put my CV out to Expats International again. Within a week, I got a telex from an old buddy from Stone & Webster days, now working for Davy McKee, the steel corporation, asking if I would be interested in working in Mexico. Yes please. I also got a call via my father in UK, from Falcon, a recruiting agency for Royal Dutch Shell in Brunei, asking if I would be prepared to go there.

It was the toss of a coin that led me to go to Mexico.

The contract was for £2,800 per month, tax free, and US$ 1,000 living

allowance, with a vehicle and accommodation provided. As Resident

Engineer, my job was to check and verify the sufficiency of design prior

to construction, and to agree heavy lift procedures for the 400 ton

Sparrows rigs used to locate the rolling and scarfing mill and the

overhead travelling crane beams.

It was this job that would change my life. Until I met Carmen, I was of the opinion that marriage was an institution. While I had girlfriends on two or three continents, I had absolutely no intentions of living in an institution. If I wanted to go somewhere, I hopped on a plane and went. I did not need to consult or feel guilty.

I courted her for a year, then proposed. My one year contract had over-run and I again put my CV out through Expats International. I received a response from a Dutch agency, asking if I would work in the Gabon on a Shell job. I left Mexico in May 1990, flew to Holland via Houston, was handed keys to a hire car and drove to Dusseldorf.

Mannesman Anlagenbau interviewed me, offered me an eye watering contract on the spot, on $9000 per month, all found, drove me to Bonn (then the West German capital) to the Gabonese Embassy for a visa, picked up anti-malarial tablets, back to Dusseldorf to the airport, to hand in the hire car and catch Lufthansa to Paris, then overnight with Air Gabon to Libreville. I flew Inter Air Gabon to Port Gentil the same day, then took a taxi to the company office. The same night, I was on a river boat heading the sixty miles on the Dianango River for Shell Rabi Field. Less than twenty four hours earlier I had been in Mexico finishing on another job and saying goodbye to my fiancée. I had not visited England for eight months.

I have to hand it to the Germans, they do not hang about on ceremony.

Mannesmann Anlagenbau: Shell Rabi Field Gathering Station & Pipeline Project, Gabon

I was working on a pipeline and central gathering station upgrade. President Bongo had taken the Saudi bribe money to turn the country Muslim. His problem was that the country was fiercely French Catholic and in late June 1990, Port Gentil revolted. The French sent in the Marines and Paratroopers to protect the oil installations and evacuate foreigners. I returned to Mexico to get married, collecting my father in the UK on the way.

French Military - Evacuation from Rabi Field, Gabon, June 1990

I returned to the Gabon in September. That same month, while in my truck on my way back from the river jetty to the camp, I had a close encounter with a gorilla. He had loped across the laterite road right in front of me. He stopped less than ten feet from the open window of my truck, stared for a moment and loped off into the jungle.

The Shell Mannesman contract was completed in July 1991 and my CV had already gone to Expats International.

Many ex-Brown & Root engineers had moved to a company called Teknica, Libyan owned under the National Oil Corporation. In August 1991 I was asked if I would go to Tobruk via Sarajevo in Jugoslavia, to check and sign off the designs prior to construction and go to site as Owner’s Representative.

When I arrived in late August the situation in Jugoslavia was deteriorating and with high inflation, the currency was devaluing by the day. Sarajevo at that time was peaceful, but there were underlying tensions between the Serbs in the town and the Bosnians.

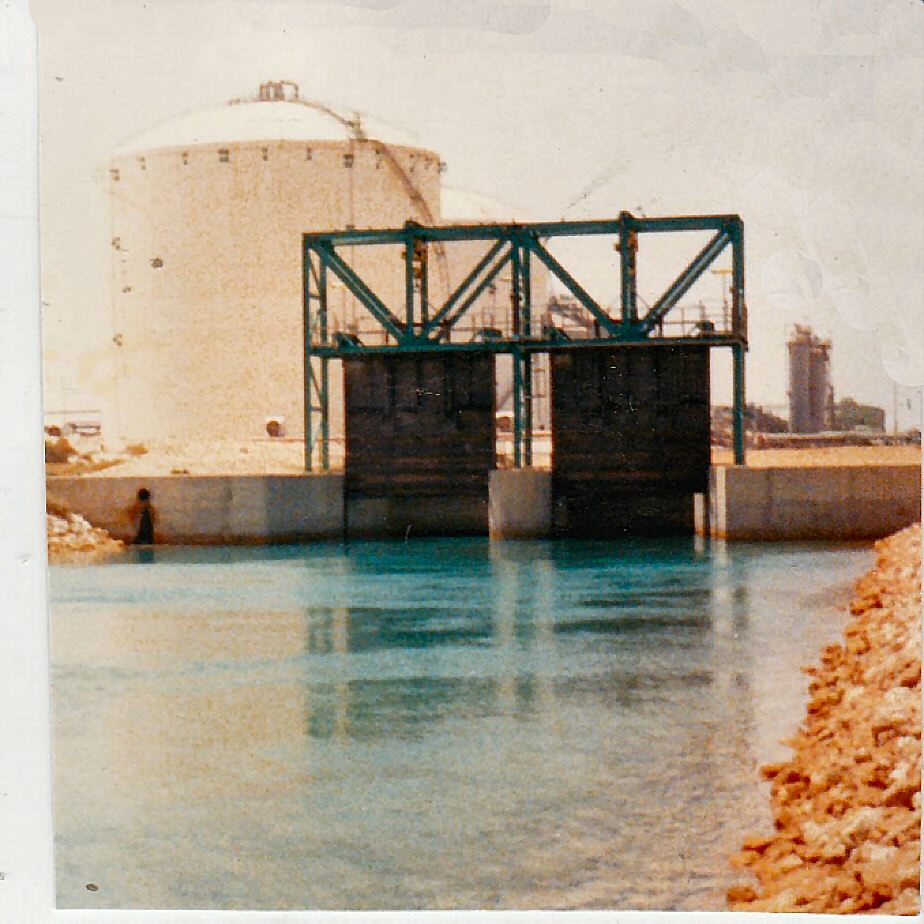

Arabian Gulf Oil Company - Tobruk Refinery Expansion Project

1991-92

The Libyan manager sent me back to Sarajevo in February 1992 to check if the steel works at Zavadovici, north of Sarajevo was still functioning. It was not. I could see from the train that the furnaces were out. The situation had deteriorated considerably. They had no formed plate for fabrication and the railway bridge at Mostar leading to the port of Ploce had been destroyed. The project proceeded with the civils and some tank welding, but the Sarajevo company PPI, the supplier, could not continue and by October 1992 they had effectively ceased to exist.

Teknica transferred me to a design office in Malta in December 1992 for the Waha Oil, Faregh Field Project, where I was engaged on designing piled support structures for gas oil separation equipment, turbo compressors, a 60 km 20 inch gas line to Zelten and a 14 inch oil line to Gialo.

A job came through in September 1993, as Principal Design Engineer on a Petronas ethylene and oil jetty at Kertih, North of Kuantan on the East coast of Malaysia for Penta Ocean of Japan. Initially based for design at Subang Jaya, Kuala Lumpur, the client had accepted my proposal for using 42 inch spiral weld raker piles instead of the verticals shown on the Instructions To Bidders. There were limited envelopes for pile driving at sea between monsoons and raker piling gave us much more flexibility in utilising the piling barges. Calculations were based on the 100 year period return wave. The jetty approach trestle would stand ten metres above mean sea level, with a breakwater to be constructed by our sub-contractor Zin Con Marine of Holland a mile offshore. The Japanese were highly organised and the jetty was completed on time in April 1995.

I went home to Mexico.

Penta Ocean - Petronas Ethylene Plant Marine Facilities - Kerih,

Malaysia

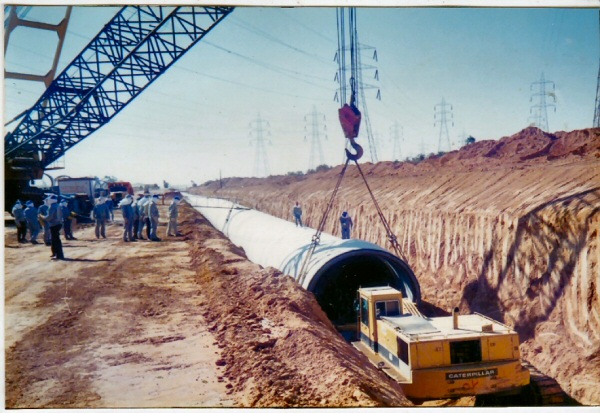

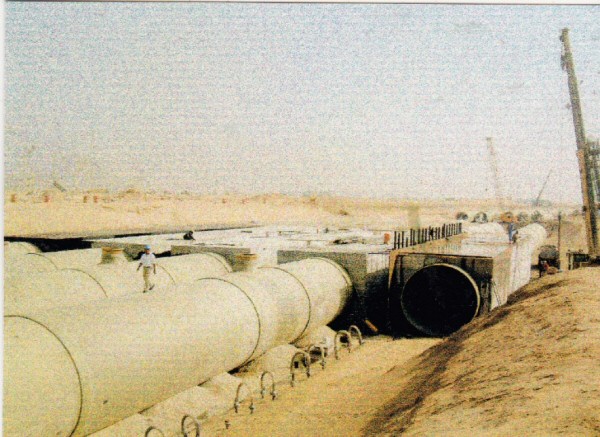

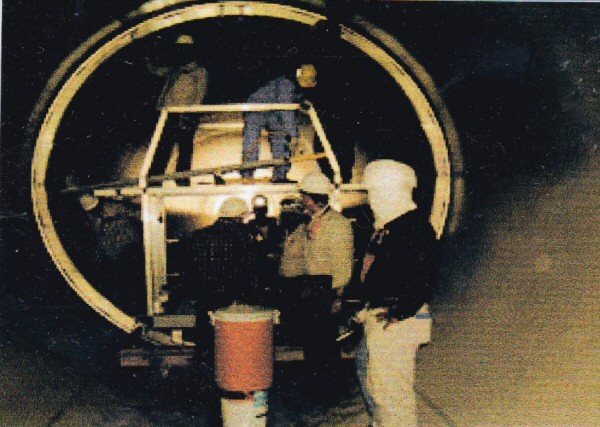

With my CV out again to Expats International, I was contacted by the Dong Ah Consortium of Korea in July 1995, engaged on construction of the Great Man Made River. They had noted my time with Brown & Root and my previous work with large diameter pipes with Stone & Webster at Ras Lanuf. They offered me a one year contract, to troubleshoot problems on phase one of First Water To Benghazi.

There were plenty of problems, largely associated with poor quality control by the Koreans. I could sense that there was deep mistrust of Dong Ah by Brown & Root, who had largely left Dong Ah to their own devices. I established a good rapport with the Brown & Root engineers in my time and left at the end of my contract, in August 1996, for work with Bechtel in Saudi Arabia.

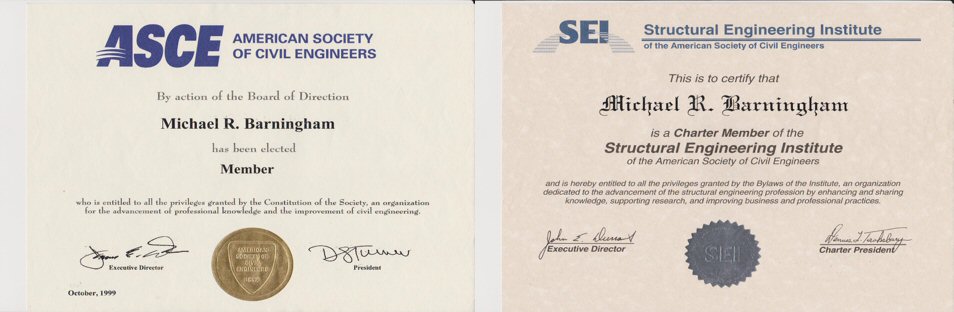

I joined Bechtel in October 1996 in Al Khobar Saudi Arabia, leading a design team engaged on a number of Aramco minor projects, at Shabah, Uthmaniya, Abqaiq, Ras Tanura and Jeddah. During my time with Bechtel the Company had sponsored me to join the American Society of Civil Engineers as a full member, going through my PE licence exam.

I had been a Member and Chartered in the Institute of Civil Engineers in Britain. Many of us were more than disenchanted with them. Their objective seemed to be job sharing and holding British engineer wages below all the other professions. They had merged with the municipal engineers. I let my membership slide, as I found them to be irrelevant to what I was doing for a living in the Oil & Gas industry.

I was transferred to Yanbu in April 1997 as Civil & Structural Project engineer for the two billion US$ Ibn Rushd PTA and aromatics plant, handing over to the Mechanical Project Engineer in December 1997.

There had been heavy flooding in Tabasco, Mexico in October 1997. In February 1998 Bechtel transferred me to their joint venture project to do follow up restoration work on flood damaged oil and gas installations for Petroleos de Mexico.

My father died the following month. After my father’s funeral, I remained working in Mexico until June 2001 without visiting Britain. I completely missed all the hoo-ha over the Millennium Bug. I had done a US Commercial Truckers Course in Florida not long after my father died and I started a family trucking business in Mexico.

In July 2001 I was back to Libya with Teknica again on Veba oil operations, as a project engineer on modifications and rectifications of oil and gas field infrastructure in Ras Lanuf on the coast, and Ghani Amal and Tibisti deep in the desert. I lived in a rented flat in Tripoli and did the hash house harriers on Fridays when in town. I met my old boss from Brown & Root RASCO days, who had risen from manager of RASCO projects to deputy head of the Libyan National Oil Corporation. I was still an expat Project Engineer but I earned more than he did. I stayed with Veba Oil until May 2004.

I was offered a Contracts Administrator’s position on the Jubail Industrial City, which Bechtel was running for the Saudi Government. US$ 12,000 per month, vehicle, flat, six months on two weeks off, plus business trips and a Saudi Multiple exit re-entry visa. I escaped every Thursday afternoon for the British Club in Bahrain, returning in time to start work on Saturdays. The work I was engaged in was around the engineering and procurement of large diameter pipes, valves and pumping systems. I visited factories in Korea, Japan and France, expenses paid on the company. All good things come to an end - I stayed with them for two years, until June 2006.

I had flown to Amman in Jordan for interview with Brown & Root a couple of weeks before my second year with Bechtel finished. They wanted me for Phase IV on design checking for the Ghadamas to Azzawiya pipeline. Roughly an eighteen month contract. When I landed at Tripoli I was met by Ken McGinley, who I had worked with at Ras Lanuf when he worked for RASCO. I had forwarded his CV to Brown & Root in 1987 and he had been with them in Libya ever since. Construction had started ahead of design and I had a lot of catching up to do. Fortunately most of the structures were standard repeats of the previous phases of the GMMR. But there was a mountainous stretch across Garb Nazariyah with requirements for more pumping facilities. By November 2008 the design was running down. I went home to Mexico.

In March 2009, an American agency contacted me about an American Aid job for a large school in Nigeria. They said that Jagal, the Nigerian company handling the school, also had large fabrication yard facilities for the offshore oil industry and they would like to talk to me. I was naturally wary of the words 'Nigeria' and 'company' in the same sentence.

I was pleasantly surprised and they made me a good offer for work on the

New American International School, to be built on reclaimed land owned

within the Twin Lakes project of Chevron Oil. Exxon Mobil and Shell also

had interests in the project. I was told that I would also be required

for oil industry works on Snake Island, owned by Jagal. I mobilised to

Lagos in April 2009, just in time for the rain season and spent a very

pleasant two years alternating between design and construction.

When I was paid off after designing and fabricating a helicopter landing pad for an oil rig, at the end of 2011 I was introduced to Field Offshore Design Engineering. They hired me as construction manager for work in Delta State on an early production facility, a seventy kilometre pipeline, wet gas receiving facilities and an LPG & Propane tank storage and loading facility.

I hardly noticed that I had reached retirement age three years ago. I

have carried on working.

And now the part everybody has been waiting for.

Conclusions ...

Will I ever retire? Possibly in a few more years, but why swop something you enjoy doing for something you may not live to regret. Besides I am funding my son through college.

Regrets. Too much time on the Air Cadets and too little study at school.

Aims and ambitions. I have already parachuted and done a bungee jump. When I do have more time and we have finished processing our Green Card for the United States, I will get my flying licence back.

Where to start? I can boast that amongst my ancestors of a century or more ago, were industrialists like my great great great uncle William Barningham, an iron and steel magnate, who was born in Arkengarthdale, North Yorkshire in 1825, one of eleven children. He was a self-made man. He ended up, in his Darlington and Pendleton foundries, producing railway lines for the fledgling railways of North America and the Empire. He was the first man to own and use a Bessemer converter in England, was one of the richest men in Britain and, reputedly, a thorough going, down-to-earth alcoholic with a vile temper. His obituary finished:

William Barningham died as he had

lived, a disappointed, exacting, unlovable man;

and those who inherit his gains have little cause to revere his memory

and those who inherit his gains have little cause to revere his memory

So money isn’t everything.

My father, my two uncles and my aunt, were all born in the same public house, The Red Lion, Langthwaite Arkengarthdale in North Yorkshire:

This probably taken on the only two

days in the year when it wasn’t raining or snowing.

Alas none of his wealth ever trickled down to our side of the family. We did seem to have a talent for global travel way back then. Three of our lot went to America in the late 1840s, two into railways from the William Barningham foundries and one into lead mining. There is a Barningham Road in Richmond Virginia, where there was a steel rail stockyard. Nathanial Barningham, then living in Swaledale, was deported to Australia in 1843 - for sheep rustling.

My father escaped Arkengarthdale at seventeen, almost a century later in 1936. He joined the Royal Marines. On 10 May 1940 he had been on the raiding party which invaded Iceland, the same day that Guderian’s panzers were breaking through the French at Sedan. He sailed to Dakar on the Ark Royal and disembarked at Gibraltar two days before she was sunk. He trained on Landing Craft and was a Landing Craft Coxswain on D-Day. He went on the Reserve in 1947 and married my mother. She had just come back from Germany, having served in 21 Army Group and on the post-war Control Commission.

So where did my inclination for travel start? I was born in St Stephen’s Hospital Chelsea London, on 7th October 1948. When I was a year old my father was recalled to the Marines for the Malaya Emergency, but instead wound up in Korea in 41 Commando. My mother and I lived in a third floor flat at No 1 Great Cumberland Place, overlooking the Marble Arch. My mother was the deputy manageress of the Euston Tavern (now called O’Neill's) opposite King’s Cross Station.

No 1 Great Cumberland Place

I am told that at two years old, in the summer of 1951, my cot was up against the open window. I had crawled out onto the window ledge, fifty feet up. The Fire Brigade arrived with the Police, before my poor mother had discovered my penchant for travel at altitude. I think she was on sedatives for a week. Were it not for an alert passer-by and the London Fire Brigade, my travelling inclination, would have ended right there.

The Bermuda Triangle is the mysterious phenomenon, famous through the ages, for all manner of men and materials vanishing into oblivion. The Barningham Triangle, is much more simple. They all seem to have vanished into pubs after service in the Marines, Army, or the police.

Thus when my father returned from Korea in 1952, he and my mother, following the pull of the family gene defect, vanished into the pub trade, first as manager of The Falcon in Clapham, and then as tenant in The Geldart in Cambridge, a Tollymache pub opposite the Co-op dairy.

The Falcon, Clapham, London |

The Geldart, Sleaford St, Cambridge |

At the age of six, I attended the Shrubbery School on Hills Road, cycling across town through the traffic in all weathers. Quite normal in my day, but I wonder what British 'elf 'n shafety' would make of that, with mummy’s little dears of today wrapped up and strapped in to mummy’s recreation vehicle.

From crawling on to elevated ledges at two, I graduated at the age of seven to scaling the scaffolding on Cambridge building sites. Ever onwards and upwards. At the Shrubbery, boys' penknives were inspected by the sports master, to make sure we kept them clean and sharp for peeling oranges and trimming bits of wood. I also presumed that he didn’t want me to stab anybody with a dirty blunt knife. Where I grew up, in the back streets of Cambridge, a penknife and a bike were essentials for a boy. Owning a watch, even one with Micky Mouse and Big Ears on it, usually meant your parents were comfortably well off.

It was at that age that I began to take notice of all the aeroplanes in the sky, around Cambridge. The father of a school friend was based at Bassingbourn, an RAF navigator on a Canberra B6s. I often stopped over at his place in the Officer’s Married Quarters at weekends while at junior school, spending my time on the end of the runway with a pair of binoculars that my mother had looted from Germany. Probably time better spent than climbing 70 feet up the scaffolding of the new Co-op bakery chimney.

I passed my 11+ and for my sins wound up here at Soham, where the next five years would prove that, at the time, I had little academic inclination. Travelling daily from Cambridge I developed a pathological hatred of buses. My mother was a devout Christian, my father not so much. I was packed off to Sunday School at St Barnabas Church on Mill Road. I really, really, hated it. I was, by the age of eleven, quite capable of my own interpretation of the scriptures. I decided on one sunny day to go for a bike ride instead. Armed with the binoculars,and an OS 1 inch map, I cycled to RAF Waterbeach to observe the Hawker Hunters based there.

It was six weeks before I was rumbled. My mother had assumed that after Sunday School I had gone round to a friend's place in Mawson Road. His mother said she hadn’t seen me. I had managed to visit RAF Waterbeach once, RAF Oakington once, RAF Duxford once and Marshall’s Airport three times. I handed back the money my mother had given to me for the collection and nothing else was said. I had learned how to read a map.

I joined the Air Training Corps at thirteen and a half and developed into an air force mad Air Cadet. I attended my first summer camp in the summer of 1963 at RAF Marham, then a V-Bomber base operating Valiants.

104 (Cambridge) ATC Squadron Summer Camp, RAF Marham, August 1963.

Mike Barningham 2nd row up, extreme left.

104 City of Cambridge Squadron was a very fortunate squadron. We had the full support of Sir Archibald Marshall. No.5 Air Experience Flight and the University Air Squadron were based at Marshall’s, a couple of hundred yards from the Squadron HQ on Newmarket Road. With Training Command at RAF Oakington, operating Varsity transport trainers, and ten or eleven other operating RAF stations within a thirty mile radius of Cambridge, opportunities for visits came thick and fast.

More and yet more ATC and the summer of 1964 saw me on Annual Inspection, with a mention in the Cambridge News.

There were four Soham Grammarians at our 1964 Summer Camp at RAF Finningley, another V Bomber base operating the Vulcans of 617 Squadron:

The four Soham Grammarians: Mike Barningham (back row, extreme left); Charles Holleyman (back row, 4th from left);

Mark Taylor (back row, 5th from right); John Shelley (back row, 2nd from right)

As Captain Speed and Captain Scott will possibly recall I paraded with the SGS Army Cadet Force, in Air Cadet uniform, with Mark Taylor, John Shelley, Lawrence Arthur and Charles Holleyman, who I had recruited to the ATC. Brian Callan, the Science Lab technician who held an RAFVR(T) Commission in the Downham Market ATC Squadron, also mucked up the khaki ranks by parading in air force blue. He ran the rifle range.

I reached the rank of Cadet Sergeant at sixteen, resplendent with Senior Cadet and Marksman badges, complete with solo Glider Pilot Wings gained on course at RAF Halton. I had amassed a total of 62 flying hours on Chipmunk T Mk 10s of No.5 Air Experience Flight and the University Air Squadron, both at Marshalls Cambridge - and in the Navigator seat of Varsity transport trainers based at RAF Oakington. I attended camps at RAF Marham, Finningley and Ternhill. I also did the ATC Outward Bound course at Keswick

|

|

My week was very busy. At six thirty each morning except Saturdays, I cleared the empties, filled the shelves, wiped the tables and cleaned the ash trays in my dad’s pub for four shillings pocket money each week.

On Wednesday evenings I paraded at the Squadron HQ.

On Thursday evenings, I cycled nine miles to RAF Oakington to hang around for an opportunity to fly with RAF Training Command.

On Fridays I paraded in ATC uniform with the SGS Army Cadets.

On Saturdays, I was up at four and on a milk float, heading for Histon, Cottenham and Rampton with a Co-op milkman who wanted to finish early on Saturdays. He took me on to help deliver milk for half a crown for the morning. I was leaping in and out of the moving open door milk truck, grabbing full milk bottles, running to the door step and returning at the run with the empties. Modern Health & Safety would probably go into cardiac arrest. By noon, I was hanging around 5 AEF hut at Marshalls in ATC uniform, or the University Air Squadron line office.

Sunday morning I paraded at Squadron HQ and Sunday afternoon I was back at Marshalls, hanging around for an opportunity to fly. Bill Ison, of the Tiger Group at Marshalls, who owned the cycle shop in Chesterton, was a customer in the pub, and I flew in a Tiger Moth on three occasions. I also passed ACF Certificate A Part I and II, with the SGS ACF.

I did manage to give grammar school my full attention on Mondays and Tuesdays, but only if nothing more important was happening. I paid heavily for the lost attention to school work later. I think that of my academic achievements at Soham, it could easily have been written of me "Sets himself ever lower standards, which he consistently fails to achieve."

Form 5T/Alpha Summer 1965 - more photos

5T photo top L-R: Mark Taylor - Colin Blackwell - Philip Rowe - Andrew Crane - John Seaton - Lawrence Arthur

upper middle: David Camps - Richard Butler - William Wheeler - Roger Creek (partially obscured) - John Bailey

lower middle: Geoff Griggs - Michael Barningham

front : Michael Murfitt - Ian Middleton - Tom Gray

image: taken by Alan Bray

formerly The Kings Arms, Ivybridge, Devon

At the time, not being remotely interested in staying at school and having neither inclination nor natural talent for anything of use in civilian life, I started applications for the armed forces.

To my disappointment, the Air Force didn’t want me in any capacity that I wanted them. I didn’t at the time see myself in the Navy.

I passed the War Office Board for the Army and was offered a limited service commission, but that would have meant going back to school at the Army School of Education at Beaconsfield to complete ‘A’ Levels and a commission through Mons Officer Cadet School. At that time I didn’t want any more school.

I passed the Admiralty Interview Board for a Commission in the Royal Marines, which only required five GCE ‘O’ Levels, presumably because nobody bright enough to pass A levels or sane enough to realise the many opportunities for serious injury, or worse, would consider the Marines as a career. However I did not pass high enough on the list of qualifying candidates for a place on the next Young Officer Entry. So I enlisted. Green Beret first, Commission later, with my eye on aviation.

Thus I joined 867 Squad of the Royal Marines - proving I wasn’t Air Force Mad, just mad. My life insurance premiums went up - my mother was back on sedatives. I told her to look on the bright side - after rejection by the RAF, I had seriously considered the Foreign Legion and the US Army.

Down to Deal in Kent, where I signed on and got the Queen’s Shilling, along with DMS boots, puttees, denims, a scrub belt and a Navy Beret, with an RM Cap Badge, plus a set of tin mess tins. I was ‘Introduced’ to one Sergeant R Davis RM. It wasn’t the bolt through the neck or the zip up the back of the head (that the collar, tie and green beret did little to conceal) that told me that I might have a problem if I upset him - and he probably got upset very easily. It was those piercing, laser eyes. His gaze was like something out of a very grisly Neanderthal science fiction movie. They could see right through you - and the man standing behind you. They also worked simultaneously out of the back of his head. The squad loosely assembled for the first group photo.

Royal Marines 867 Squad, April 1967: Mike Barningham front row, 3rd from left

Thirty three started. How many would finish with the 867, if at all? The smiles were very quickly wiped off our faces. The object of the first ten weeks training at Deal was to get you physically fit and mentally conditioned for what was to come, or back-squadded - or out. The process involved killing any lingering civilian characteristics and extinguishing any thoughts of a glamorous image. Life was harsh. PT in the Gymnasium every day except Sunday. Pull-ups, sit-ups, rope ascent to the roof, and running as a squad - drill followed by more drill. Weapons training, the range, kit musters, bivouacking, yomping up to Cold Blow field. Break camp, make camp. The pace increased as the weeks passed.

Six weeks in, I got into sailing at Deal and crewed one of the Corps' yachts, the Sarie Marais, from Dover to Boulogne over a long weekend. I had phoned my parents and let them know I was sailing to France. As things turned out I probably should not have done that. With the Royal Naval Education Branch Lieutenant Commander as skipper, seven of us had sailed out of Dover Harbour for a night crossing on the Thursday evening, tied up alongside amongst the Boulogne fishing fleet and proceeded ashore to immerse ourselves in French culture.

The Colonel of the Depot, H. Maude, had sailed over in his own yacht with his wife, a day behind us. He tied up alongside the Corps yacht and came aboard, to find us all seriously four sheets to the wind after a liquid French cultural experience still very much in progress. “I think it is time that you started back for Dover.”

It was not a hint, or a birthday greeting, it was an order. We slipped and followed the Colonel and his lady out of the harbour. The sea was cutting up rough and it was night, the radio had failed. The skipper wore quite thick glasses. He decided to do the sensible thing. Without radar or radio, in bad weather, with an inexperienced crew and with oil tankers plying the Channel at ninety degrees to our course, we went about, put back into Boulogne, tied up alongside and went back on to the French culture to wait for a break in the weather.

The Colonel carried on, oblivious of our change of course, arrived in Dover. He waited ... and waited ... and waited. No Sarie Marais. He couldn’t raise her on the radio. He reported to the Harbour Master, who sent out a shipping alert. It made the national press, ‘Marines lost at sea.’ My mother saw it and was back on tranquillisers. The Boulogne Triangle was not unlike the Barningham Triangle - we weren’t lost, we had just vanished into a French pub. When we got back the following day the Colonel was not at all amused. The Lt Commander took all the flak.

The remainder of my time at Deal passed without incident. We had managed to complete our seamanship training at HMS Bellerophon, Whale Island in Portsmouth, living aboard a World War II Corvette, the Volage, with mess facilities on board HMS Belfast (these days moored in the Thames). We were becoming bilingual, picking up 'jack speak' - where toilets were the heads, the padre was the sky pilot and RM officers were pigs.

After seventeen gruelling weeks 867 Squad marched through Deal to the station, to proceed to Infantry Training Centre Royal Marines Lympstone. My sixth home. We had lost some on the way and picked up some back-squadded individuals, including two who the judge had given the option of five years in jail or nine years in the Corps. They were fast coming round to regretting their decision.

867 Squad Royal Marines August 1967 - 28 of the originals left

We disembarked at Lympstone station and were met by one Sergeant MacMillan, otherwise known as the Poisoned Dwarf. Sergeant Davis was a pussycat compared to MacMillan.

The object of B group training, more accurately described as violent physical abuse, was to see if they could make any of us crack. The secret here was a warped sense of humour. You would always mock the afflicted, sympathy was for civilians. They were relentless and life became tougher and tougher. We spent a lot of time on Woodbury Common, though why they called it a Common I will never know. Although there were no fences, civilians never went near the place. It was a plantation of thorn bushes, specially designed, cultivated and arranged to guarantee penetration of combat gear no matter in which direction you crawled.

You slept whenever you could, you did not know when the chance would come again. It rained nearly incessantly that year, to magnify the discomfort. We were perpetually saturated. If there was a dry day, they would find a manky stream for us to crawl through. When we weren’t in the field there was the assault course, the gym, followed by more night exercises on Exmoor and Woodbury Common, and more weapons training. A few more 867s dropped out and we picked up a couple more back-squadders.

We went to RM Hamworthy in Dorset for Small Boat and Landing Craft training and to Jennycliff in Plymouth for Cliff Assault Training.

A marine in training would burn 3,500 plus calories per day. Food is nothing but fuel. You never threw food away, you had to carry it and throwing it away would mean you had carried it for nothing. The training seemed to go on without end, but it did end after thirty four weeks with the four Commando tests and Passing Out parade.On the first three tests you carried twenty four pounds of equipment and a rifle. All tests were completed the same week:

- The first was an Endurance Course comprising nearly dry tunnels, a full immersion water tunnel and a four mile run sopping wet down to Lympstone.

- The second, a nine mile speed march in ninety minutes, was followed by immediate scored rifle range. Even if you completed the speed march in time, if you couldn’t shoot straight at the end of it you would fail.

- The next day, the third test, a combination of the Tarzan and Assault courses, with 13 minutes to complete it. You go flat out, any hesitation and you would fail.

- The next day the killer thirty mile march, carrying 40 pounds of kit, plus a rifle. That year an outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease on Dartmoor meant that the thirty miler would take place on the roads. So the impact of running and speed marching thirty miles, in under eight hours, with full marching order, without the cushioning effect of soft ground, meant that everybody who finished did so with a green beret on top of the head and blisters on the feet. Two didn’t finish.

867 Squad Royal Marines December 1967 - 21 of the originals left

I was a Candidate in Waiting for a commission from the day I got my green hat. But first, I was to sample the delights of a tropical paradise, when my name went up on orders for a draft to 40 Commando in the Far East. I was thinking Chinese Birds and WRAFs, Wrens and WRACs, but not necessarily in that order. Was I in for a shock.

I gleefully ascended the boarding steps of the British Eagle Britannia, a four engine turbo-prop, departing Heathrow. We refuelled at Istanbul and Bombay (Mumbai), landing at Paya Lebar in Singapore. I had reached journey’s end and arrived in the land of the midnight fun. Or so I thought. Still jet lagged, I was rushed to Sembawang airfield, half asleep and clattering around in the back of a three ton truck. I was greeted by an irritated storeman with: "We are rear party and you are not. The unit is up country. You leave tomorrow, at 0700. You are joining C Company."

Issued with a Self Loading Rifle, Machete and the usual Olive Green fashion array which was topped off with a floppy hat, I stood resplendent in the British stores speciality of canvas and crepe self-dissolving jungle boots. Unlike Nancy Sinatra, we found out the hard way that these boots weren’t made for walking. In fairness the canvas never rotted, there wasn’t time for it to rot. The glue dissolved in warm water. Not surprisingly in the jungle (or Ulu) there was rather a lot of it.

Not the Kuching Hilton

The sheer luxury of the Kuching Hilton was not for me. I joined 5 Section, 8 Troop, C Company 40 Commando Royal Marines. Amongst the flora and fauna I was welcomed by my section corporal. Make yourself at home is what I thought he said. What he really said was make yourself a home. I was paired off with the lead scout, who carried a much coveted 5.56 mm AR15 Armalite rifle which was fully automatic, rather than the 7.62 mm SLR which was not and weighed twice as much. Weight in the jungle was your enemy, we even cut most of the handle off our tooth brushes to reduce weight.

I made the fatal error of asking how I could get an Armalite. The troop sergeant overheard and asked if I really wanted to swop my SLR for another weapon. “Ooh yes please.” Straight in it. They took my SLR and handed me the Section’s General Purpose Machine Gun, three times the weight of an SLR. The only consolation was that I was guaranteed to hit something if I ever had the misfortune to use it. As I was a Candidate in Waiting for a Commission Sergeant Frank Gilhooley took perverse pleasure in giving me the full benefit of his repertoire of undiluted hatred of officers, actual and potential.

Home is where you make it

This was home on and off for five weeks when I was not out on armed nature walks strolling through the Ulu, dissolving British jungle boots.

I had been issued with Air Ministry Pamphlet 214, written by an expert, to alert me to the dangers of the jungle. One paragraph was devoted to what you did if confronted by an elephant advancing on you - “Run downhill.” So there I am waist-deep in water in the middle of a rice paddy, thirty pounds of GPMG plus ammo slung round my neck, this big grey thing is getting bigger and I am supposed to look for a hill to run down. The Navy had gained a new item in jack speak when Chad Valley came out with games for children which didn’t do what it said on the box. Something that didn’t work became Chad.

The grief felt after the loss of a pet can be every bit as painful as that following the death of a human, so why didn’t we take it so seriously in the Marines?

It really depends on the pet. Here is one reason:

I did managed to ‘procure’ a pair of stitched Australian jungle boots which were fit for purpose, just in time to no longer require them as we embarked on the Commando Carrier Albion to sail off to the Gulf of Aden where DMS boots would be the order of the day. Harold Wilson had decided to cut the cost of us being in Aden from £60 million a year to £12 million. I completely failed to see why we were paying anything at all as they had moved into the Russian sphere of influence, but there were still Europeans left in Aden and we were being sent to stand by to get them out if things got nasty.

40 Commando embarked on HMS Albion for the Gulf of Aden, March 1968

Fortunately peace and tranquillity prevailed and we sailed to Mombasa, a place with every disease known to man and quite a lot that were not, then to RAF Gan and back to the Far East and Singapore.

Continual exercises in the Malayan jungle became the norm, until we sailed on the Landing Ship Logistic Sir Geraint to Australia, via the Timor Sea and New Guinea, where we did a nine mile speed march at 95 in the shade. The locals thought we were crazy. Three cases of heat stroke proved that they were right.

C Coy 40 Commando 9 mile speed march Port Moresby, New Guinea. October 1968

On to Australia, for exercise CORAL SANDS, a huge SEATO affair, involving the armed forces of four countries. 40 Commando were landed at Shoalwater Bay near Rockhampton. We had been warned that Australia had more crawling nasties than everywhere else on the planet put together. We were warned to watch out for the snakes particularly the Coastal Taipan - which if you were bitten by one, without the antidote it would prove fatal. The problem was that there were one hundred and four known variants.

Friendly Queensland local. Coastal Taipan come to say hullo.

We were told that if bitten you must kill the snake and bring it back, so they could administer the correct serum! We were also told that we had about two hours to get medical attention. I saw two Taipans and a King Brown, which was OK. It was the ones that you didn’t see that would be the problem.

We chased enemies simulated by 800 Gurkhas all over the bush. Over the following week I think we caught one. Then on to the important part of the exercise. Shore leave in Brisbane.

The Aussies threw the town open to us and by and large, we behaved ourselves. The girls, the pubs and the climate were great. Several marriages were to occur as a direct result of our run ashore in Brisbane. How different from Britain, where the sign ‘NO SOLDIERS OR DOGS,’ was sported unchallenged in some pubs. I was getting the first glimmer of where I probably wanted to go when I left the Corps. When we sailed for Singapore, a dozen marines were AWOL. Most were arrested and returned, but I think a couple of them are still missing. Many British ex-service personnel were to find a home in Australia.